ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works (this note)

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

In this note, I survey the vexed issue of the evidence base for anti-corruption. It has long been a source of tense relationships within all donor agencies, bilateral and multilateral. Any aid provider, at some point, gets caught in the fixed glare of a political master who asks the simple question: “what works?” When the answer comes back, “we don’t really know,” sparks often fly.

The frustration is palpable and understandable, and hasn’t really changed over the 20 years that I have spent immersed in the business. A country programme director once brusquely demanded of me, “just give us the two-pager that tells us what we need to do and we can get on with it.” They saw it as any other technical development problem, like improving education or getting crops to grow.

Our inability at the centre to have an authoritative story to tell – or even just to point our folks in one or two clear directions after two decades of investigation – is one of the stark hallmarks of our field.

This note does not provide the answers, or perhaps much comfort. But I hope it lays out some of the factors that should be borne in mind. (In a later part, I will propose ideas for a new framework that donors ought to think about in structuring their in-country approach, drawing on some of the lessons and insights that follow here.)

Framing the problem

The donor effect

A vital first factor to appreciate is the need to differentiate between (i) the intrinsic issue of understanding what it is that beats corruption and (ii) the ways in which donors think and operate on the issue. These two have almost never aligned, and account for much of our seeming failure to succeed.

It is one thing to seek to understand the pathology of corruption and how to construct a response. It is a very different exercise to craft that countermeasure as a donor intervention, since donors work within their own tight world of thought processes and methods that in practice have made success extraordinarily elusive.

I drew attention to this disjunction in a piece written shortly after leaving DFID entitled, perhaps provocatively, 5 reasons why aid providers get it all wrong on corruption. Its purpose was to stress a point that is often lost in the search for remedies: that the very working methods adopted by donors themselves shape the response and hugely weigh against the chances of success.

Getting the objective right

A second factor in calibrating overall ambition is the distinction between eradication and control. The early years of the anti-corruption effort was marked by calls for corruption to be eliminated, eradicated, entirely got rid of. This later shifted to a more realistic objective of mitigating what is accepted as an ingrained social phenomenon.

Setting up the ambition for a society to be ‘corruption-free’ both flies in the face of human experience and potentially diverts energies away from smaller level successes that would still make an important difference. No police officer ever joins their force thinking realistically they will eradicate crime. Doing as much as possible to bear down on it has its own value. As the old saying goes, letting the best be the enemy of the good is a perennial problem in scoping anti-corruption ambitions.

As the box below shows, corruption has existed since the first humans collected themselves into societies. Indeed, taking Finer’s superb volumes on The history of government from the earliest times as our roadmap, the term ‘corruption’ first appears just 15 pages into the 1,700 page narrative: so after only 0.9% of the story of human governance, we encounter corruption. That’s how ingrained it is in human nature.

Things weren’t any different in ancient times

Sumer, 3000BC – The very first recognised civilization records the ensi (ruler) of Lagash abusing the 'God's oxen' to plough his own onion fields, and that these onion fields were located among the best fields. The ensi's entourage is reported to have appropriated the head priest's barley ... and head steward of food supplies 'felled the trees in the public garden and bundled off the fruit.'

Ancient India, 300BC – Brahman Prime Minister of Chandragupta writes of ‘at least forty ways’ of embezzling money from government.

Ancient Greece, 400BC – Plato talks of bribery in The Laws: ‘The servants of the nation are to render their service without any taking of presents … To form your judgment and then abide by it is no easy task, and ‘tis a man’s surest course to give loyal obedience to the law which commands, “Do no service for a present.”’

Arabia, 14th century – Abdul Rahman Ibn Khaldun writes of ‘the root cause of corruption [is] the passion for luxurious living within the ruling group. It is to meet the expenditure on luxury that the ruling group resorts to corrupt dealing’ [so not much change from today].

Examples from The history of government from the earliest times (Finer, 1997).

It's all connected

At the heart of the evidence conundrum (for aid donors at least) is the reality that no intervention on any single dimension of the problem can hope to have a transformative effect on the overall landscape. Yet donors find themselves doing precisely that. Their own operating systems that demand clearly bounded projects specifically targeted on discrete elements of the system cannot accommodate the multifarious nature of corruption’s grip. Donors partition when the nature of corruption demands association.

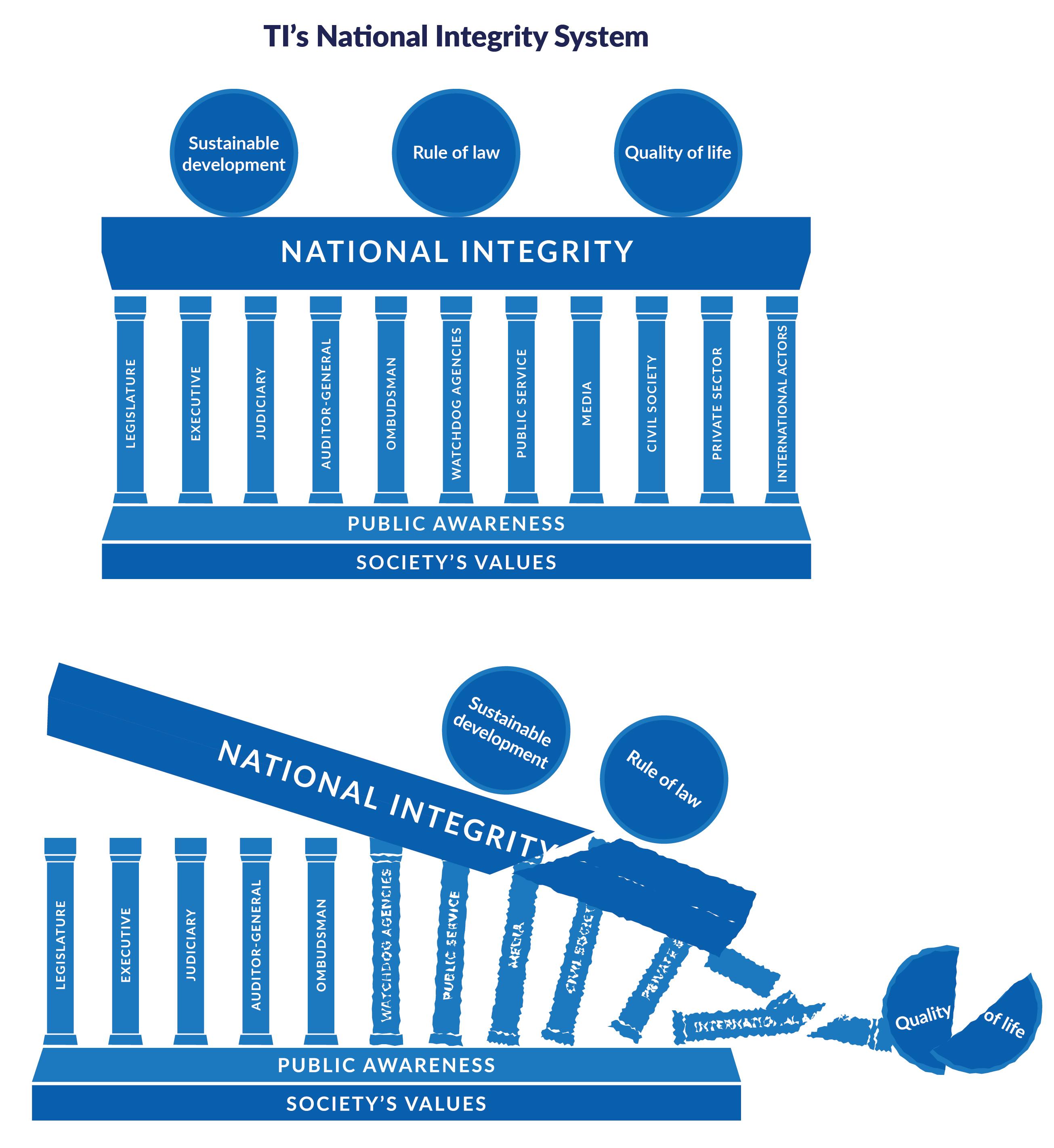

Appreciating the connectivities needed for bearing down on corruption at a society level is crucial. It has been famously illustrated by Transparency International’s temple diagram, showing how vital each pillar is to the whole edifice … and the consequences for ignoring the relationship.

Finally though … it may not be in our hands at all

Leaving aside the technicalities of how donors organise themselves, there is increasing evidence that we may all be on the wrong track anyway. Intriguing work by researchers looking at how societies have historically moved from being largely corrupt to largely uncorrupt suggest that it may not be from direct action against corruption at all.

Bo Rothstein’s celebrated study from 2011 looks at the transformation of Sweden from a corrupt 18th century society to the relative paragon of cleanliness seen across the Nordic world today. It points out that none of the reforms that were instrumental in changing the social norm away from corruption were actually explicitly targeted against corruption. The key building blocks seemed to be education, openness of access to public positions, and related freedoms in trade, universities, and political representation. Similar findings have emerged from other work looking at a suite of ten countries that have recently seen a transition from a corrupt past. All did so for intensely political reasons – the reduction in corruption came as a by-product.

The U4 review

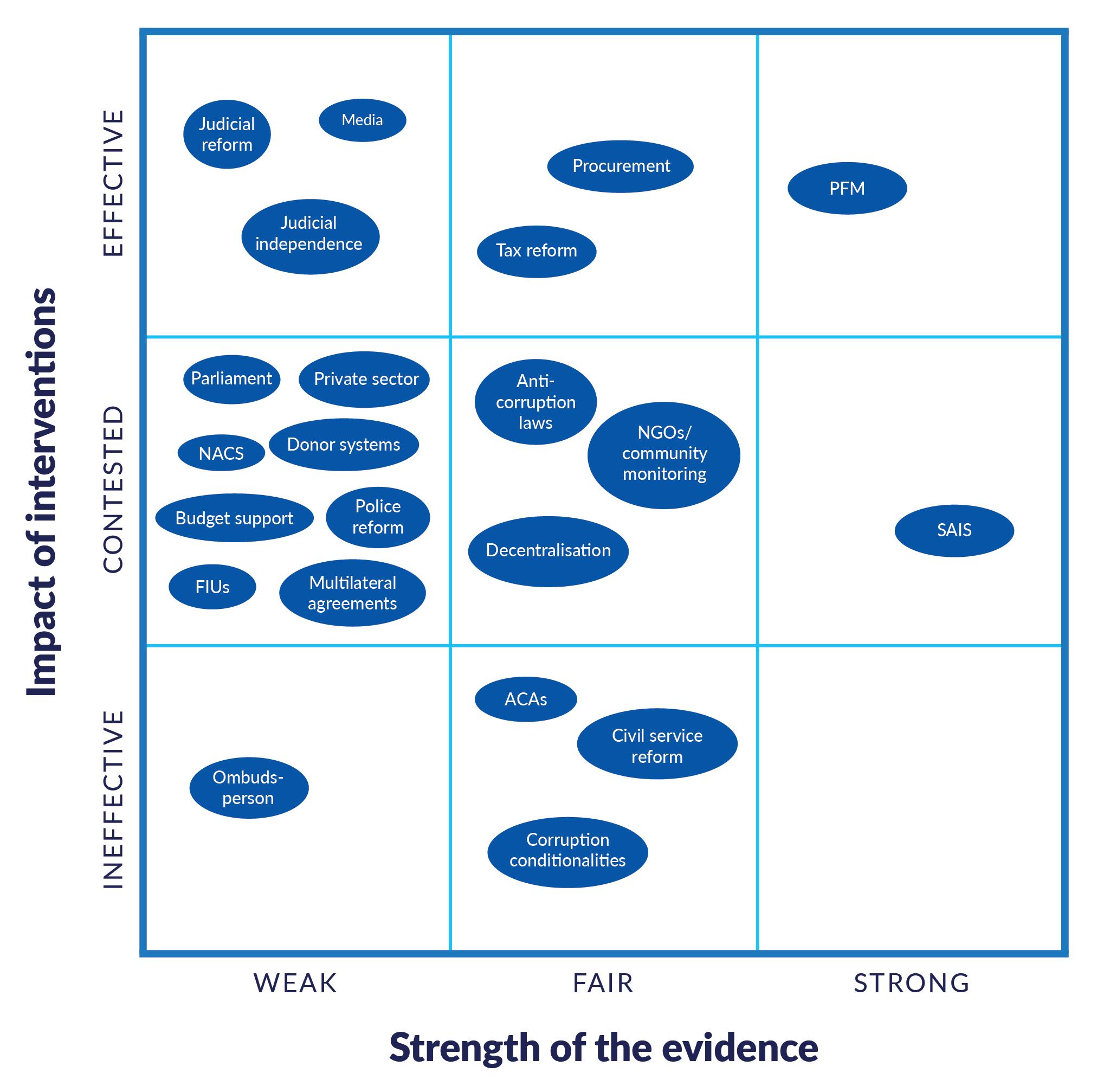

Until DFID commissioned this review in 2012, the donors collectively did not have any overall appreciation of the state of the evidence picture. While it remains a valuable read, its bigger message presents more questions than answers. It showed that several favoured donor responses, such as anti-corruption commissions, public service reforms, and anti-corruption conditionality were clearly not working. And it could point to almost no area where there was strong evidence of success either.704cf574a05a

The matrix below summarised the position. Almost everything donors were doing had little convincing evidential backing. For most, there was ‘contested’ evidence for effectiveness (in other words, we could not tell whether what we were doing was having the intended impacts) and even that was based on very few quality studies.

This presents a depressing picture, particularly for those who – like donors – are seeking the kind of ‘transformational’ and ‘ambitious’ programming that our political masters tend to demand.

It also is striking for revealing another facet of the donor approach which likely contributes to lowering the chances of success. The ‘atomisation’ of donor inputs, as vividly shown here in no fewer than 22 bubbles, illustrates how donor practices partition their responses into discrete separate interventions. When we appreciate the inter-connectedness of corruption in any society, it is perhaps not surprising that the donor approach exhibited above – with its segmented activities – has yielded such little reward.

It is rare for donors to establish cross-institutional approaches. DFID had some examples in Ghana, Tanzania, and Uganda where making connections between relevant parts of the system was a deliberate feature of the design – but these tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

With donors more hard-pressed than ever before to demonstrate rapid results to satisfy domestic worries over the value for money of their development aid, it seems unlikely that this state of affairs will change anytime soon.

Lessons – and reflections for the future

Four strategic lessons emerge from the history of our endeavours so far; each a challenge to the orthodox methods by which donors do their business:

- That the governments we deal with are part of the problem, and need to be seen as such. Donors need to stop deluding themselves that their ‘partners’ share an equal ambition to tackle corruption.

- That ‘politics’ matters. A purely technocratic approach, which donors are most comfortable with, will not succeed.

- That there is a need to both repair weak systems and the incentive structures in society. Currently, in many developing countries, malfeasance is incentivised over integrity, and manifests itself as impunity.

- That the interdependencies of institutions matter.

We shall reflect further on this in the tenth note where we suggest ideas for a radically new approach.

Where does this leave our current favoured methods? To conclude, here are a few personal reflections on some of the orthodox solutions we donors have tried over the years.

Anti-corruption strategies

Writing them has often been a totem for donors. However, in practice, the lengthy process and detailed development of plans has often turned out to be a perfect displacement exercise for governments from actually tackling the problem. There are many examples of expensively produced strategies that remain largely exercises on paper. We should be cautious of the merits of prolonged and grand strategising.

Anti-corruption commissions

Likewise, the donor push to create these stand-alone agencies has rarely reproduced the success of their progenitors (Hong Kong, Singapore), because the conditions for success in those early examples (well-resourced, strong leadership, absence of political interference, strong political backing, and sustained endeavour) have never been replicated in developing countries. Perversely, anti-corruption commissions have become absorbers of the formal anti-corruption responsibility, leaving other institutions able to feel that corruption is not their issue, and all too often leading to a vacuum in the national response when the anti-corruption commission gets neutered by the governing elite.

Anti-corruption laws

Passing legislation is necessary, but not sufficient. Adequate law is the starting point, not the end. Implementation is everything. Increasingly, international monitoring is taking on this ‘effectiveness’ question (The 4th round of the FATF review process, for example, measures impact, as does the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.) The review process for UNCAC, however, is currently only at the initial stage – checking formal compliance with the Convention of national laws as written. It will be some time before we get genuine assessments of practical implementation.

Asset declaration

Systems for prominent public persons to declare their assets is a popular response mechanism, but have in practice been plagued by two pitfalls in design. Drawing too wide an ambit for inclusion stores up huge problems (in some systems every public servant is required to file a return). First, the more that needs to be collected, the larger becomes the storage problem and the bigger the problem of chasing non-filers. (It is important that those not filing are pursued. If not, it is quickly seen that non-compliance carries no consequences, and the system begins to fail.)

However, these efforts displace the more important focus on verifying the accuracy of declarations that have been collected. Again, experience shows that the strength of asset declaration systems lies in the verification. If respondents come to understand that authorities are not checking returns, the process quickly becomes formulaic and of little practical effect – with false declarations simply going undetected.

A more streamlined system that reduces the ambit of collection to the main risk levels in the public service, vigorously vets returns, and takes firm action when required seems to be the most effective way of working. But few countries have managed to achieve this, preferring to draw publicity and a ‘scare factor’ at the outset with the breadth of the coverage – and then being surprised when the whole edifice becomes unworkable a very short time afterwards.

Public service reform

Donors do not have a good track record in this area despite decades of endeavour. They have failed in their ambition to instil a public service ethos into civil servants who are poorly paid, work within a weak control system, and have scope for exploiting for personal benefit their interaction with the public. Technocratic reforms, such as salary improvement, ‘capacity building,’ or extensive and expensive HR performance management systems are favoured donor approaches in this process. But these have rarely taken root, not least because donors have not been able to absorb into their programming techniques the wider factors that shape the motivations of public servants, in particular the incentives operating on them.

Cultivating a public service ‘ethos’ – buttressed by stronger constraints coming from service users – is vital to rooting out corruption inside bureaucracies. Donors are far from understanding how to do this.

Vulnerability assessments

These, and all similar types of analyses, represent the donors’ comfort blanket. Knowing more about institutional weaknesses is, unarguably, a good thing. The problem is that it too often stops there. The key experience with such assessments is that they are not followed through. Energy tends to dissipate once the analysis has been done (with donors often keen to move on to more analyses – since they’re an easily measurable indicator of anti-corruption ‘activity’ – rather than spend time on the harder and longer effort to ensure that the findings are dealt with). Like asset declaration mechanisms, the lesson to be learned is that follow-through is vital, and often missing.

Information

An often-missed element is the importance of home-grown data and information. It is too easy to rest on externally-generated material, such as global surveys like the annual TI Corruption Perceptions Index. These can serve well when the host authorities are willing to accept them as inputs into the national dialogue. But, if they don’t, it becomes too easy to dismiss the message they convey with claims that they are ‘foreign’ views, concocted by hostile interests seeking to undermine the government. The argument shifts focus from the substantive one – corruption – to an often sterile one debating methodologies, a distraction that some governments happily employ to dilute attention from the real issue. A key lesson for donors is not to fall into this trap. Cultivating capacity to produce home-grown analyses, data, and statistics, by CSOs, academia and media, can take away this easy escape route for governments. It is, however, a long-term endeavour, requiring patience and perseverance.

Donor co-ordination

Governments facing challenges on corruption are adept at divide-and-rule strategies to all-comers, donors included. It should not surprise donors that they can find themselves getting played off, one against the other. And, as we have seen in earlier pieces, all the operating practices of donor agencies tend to work against enabling a concerted and sustained collective stance from donors in any location.

It is curious that UNCAC has never become the organising framework around which collective donor action can cohere in a country. With a little effort, it could be. The review assessments that have already been done for most countries to set out its needs against what UNCAC requires could lead to a clear set of actions identified for support. Enshrining this in an ‘UNCAC Delivery Plan’ could provide the clear and comprehensive agenda that is so often missing and a mechanism for each donor to make its contribution to that agenda in a co-ordinated way. This could bring many advantages: give coherence to the overall effort, address the interdependencies that are now seen to be so important, and reduce the opportunities for corruption to slip between the cracks as it too often does in the current way of working.

A final note…

There has been no shortage of thinking done about corruption. Since the creation of U4 nearly 20 years ago, the analysis available for donors has moved significantly from abstract and theoretical musings to much more practically-oriented thought. That has been a huge step forward. But there is still a long way to go. It is, however, often not any shallowness of thought that has been the problem. Increasingly it is clear that, for donors, the conclusions the evidence is suggesting are inconvenient – that donor ways of working are simply ill-suited to the task.

That is the challenge that lies before us.

–––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works (this note)

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

- Only one area – public financial management (PFM) – appears to be both successful and have a strong evidence base to prove it. But this is thought to be more due to there simply being a larger body of studies on PFM, compared to other interventions, on which to draw.