Query

What are the main corruption risks, with a focus on non-financial corruption risks, in Egypt?

Background

In the wake of the Arab Spring, Egypt still struggles with numerous political, societal and economic challenges despite experiencing several transitions and efforts to democratise and strengthen its institutions. The incumbent president, Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi, has been in office since 2014 after ousting the former president in 2013. Egypt’s political landscape is marked by the crackdown on dissent, with limited political freedoms and serious human rights concerns (Freedom House 2024). Social media is monitored, and dissenting voices are often silenced through legal and extra-legal means.

In December 2023, al-Sisi secured a third term with nearly 90% of the vote in a process reportedly marred by repression and electoral manipulation allegations (El-Ghazaly Harb 2024). At the same time, rising domestic and foreign debt pose a challenge to the fiscal stability of the country despite recent government actions and support from international lenders, including the 2024 $5 billion loan increase from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Saleh 2024). The government heavily subsidises food and fuel, and in May 2024, it decided to increase the price of subsidised bread by 300%, affecting two-thirds of the population which rely on the programme (Abdallah and El-Safty 2024).

Since 2016, the IMF has approved billions of dollars to bring reforms through emergency loans and programmes to Egypt, particularly for ‘implementing key structural reforms to strengthen transparency, governance, and competition’ as well as the privatisation of state assets (IMF 2016). Nonetheless, despite efforts to promote greater integrity, such efforts fail to address concerns about transparency in military-owned companies which is a key concern in the country. Although there has been recent progress with the IMF (2024) now requiring private sector-led growth and a more level playing field between state entities and the private sector, the impact of these changes has yet to be seen.

The Egyptian defence sector exerted enormous influence in the political and economic spheres of the country since the 1980s (Human Rights Watch 2020). The military owns and runs manufacturing, agriculture, food production and resource management businesses in the country. Experts note that the president ‘transformed [the military’s] scope and scale role into an autonomous actor that can reshape markets and influence government policy setting and investment strategies’ (Sayigh 2019).

In February 2024, the Egyptian authorities enacted new legislation which solidifies and expands the already extensive powers of the military over civilian life in the face of an economic crisis, posing a significant threat to fundamental rights and freedoms. It will allow armed forces to replace police, civilian authorities and judicial functions (Human Rights Watch 2024b). In addition, the establishment of pro-state private security groups, such as the Falcon Group, run by retired army generals, have been assigned to secure potential areas of protest in universities, airports and downtown Cairo (El-Ghazaly Herb 2024).

Furthermore, the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas since 2023 has not only deepened Egypt’s political and diplomatic difficulties, but also significantly affected strategic economic sectors such as tourism, gas exports and the Suez Canal revenues. Tourism is expected to be heavily affected by the conflict, which prompted a wave of cancellations in bookings (Chung 2023). Israel’s temporary halt of the Tamar gas field also led to a 50% drop in Egypt’s re-exports of gas revenues (Cafiero 2024).

The absence of an independent judiciary and robust anti-corruption agencies consistently undermines efforts to curb corruption in Egypt. High-profile corruption cases rarely result in substantial penalties, creating a solid perception of impunity for those in power. This environment of corruption not only erodes public trust in the government but significantly deters foreign investment and hampers economic growth.

Extent of corruption

Initially categorised as a moderate autocracy, according to the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI), Egypt saw a mild improvement in democratic status between 2006 and 2014. This peaked at a democracy status score of 4.92 (with 10 being the highest value) in 2014 when the national anti-corruption strategy was launched. Since then, the country’s democracy index consistently declined, transitioning into a hard-line autocracy in 2016 with a score of 3.93 and further dropping to 3.42 by 2024 (Bertelsmann Foundation 2024). This erosion of democratic norms is mirrored in the falling scores for independent judiciary assessments, which also peaked at 6 in 2014 but halved to 3 by 2024. The BTI notes that ‘Egypt lacks distributive justice, fair competition, equal economic participation rights and rigorous anti-corruption policies’ (BTI 2024).

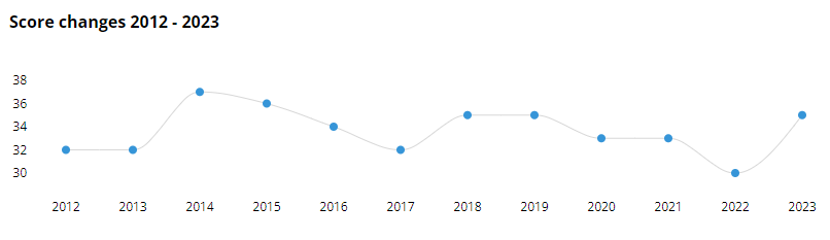

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) corroborates the BTI findings, indicating that the country’s performance has been consistently troubling, with deep-seated issues with corruption across various sectors. Egypt’s scores have remained lower over the past decade, typically between mid-20s and mid-30s. In 2023, Egypt scored 35 out of 100 and ranked 108 out of 180 states, indicating a perception of high rates of corruption (Transparency International 2023). This score places Egypt in the bottom half globally.

Figure 1: Egypt’s CPI score from 2012 to 2023

Transparency International 2023

The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for control of corruption, ranging from -2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong), consistently shows negative scores for Egypt. In 1996, Egypt’s score was -0.47, which worsened slightly to -0.58 in 2004. By 2013, the score had further declined to -0.81, reflecting a worsening perception of corruption. As of 2022, the score stands at -0.68. These persistent low rankings and pessimistic estimates highlight Egypt’s challenges in establishing effective anti-corruption measures and promoting transparent governance (Worldwide Governance Indicators 2022).

Table 1: The Worldwide Governance Indicators (-2.5 indicating weakest to +2.5 strongest) for Egypt in the years 2012, 2017 to 2022:

|

Indicator |

2012 |

2017 |

2022 |

|

Voice and accountability |

-0.77 |

-1.25 |

-1.45 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.68 |

-0.53 |

-0.45 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.54 |

-0.45 |

-0.26 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.58 |

-0.50 |

-0.68 |

Finally, Egypt ranks in the bottom half (with 10 being the highest score) on the ERCAS Public Integrity Indicator. Administrative transparency (2.13 out of 10) and the freedom of press component (2.12 out of 10) are sectors ranked particularly low. ERCAS’s corruption forecast for Egypt notes that, despite the country progressing well on budget transparency, the judiciary’s attempts to resist political intervention was unsuccessful (ERCAS n.d.). In addition, the army remains above the law and repression of the media and civil society made progress difficult (ERCAS n.d.).

Forms of non-financial corruption in Egypt

This Helpdesk Answer focuses on non-financial forms of corruption81c81d393b21 in Egypt. This encompasses exchanges that do not involve monetary transactions but predominately entail the abuse of power or public office for personal or political gain. This type of corruption manipulates political, judicial, and social structures to bolster the political regime, while simultaneously undermining institutional integrity and crushing political dissent.

Abuse of power

The abuse of power a prominent feature of the Egyptian political landscape. Since the 2013 coup, the military and intelligence agencies have dominated the political system by undermining democratic checks and balances, with power flowing from the president to his allies in the military (Freedom House 2023). There were violent crackdowns on any opposition, with reports made of government security agents physically attacking journalists or political dissidents that openly criticised the regime (Magdi 2023).

Through patronage networks and the overlapping of roles within the political class, the military cemented their power to gain economic privileges and hamper scrutiny by independent citizens (TI UK 2018:16). They have done so by ensuring there are a high number of military officers in senior positions; passing legislation to continue granting themselves ever-expanding rights; brutally supressing opposition; and carrying out a public relations campaign aimed at increasing public trust (TI UK 2018:16). The military also has the power to appoint local government structures, including in cities, boroughs and councils (TI UK 2018:16).

Trading in influence

Leveraging one’s position or connections to influence actions or decisions is common in Egypt, due to the intertwining of political power, military influence and economic interests. Market mechanisms are distorted through unfair competition, market monopolisation, price distortion, misallocation of resources and unequal access to opportunities. Since the inception of Infitah215146a82413 in 1967, Egypt’s economic liberalisation was characterised by political corruption and a lack of transparency, that attempts to exclude certain groups (particularly Islamist-leaning groups) from state and big business patronage networks (Adly 2020).

The current government’s influence permeates various sectors, from business to politics, consolidating economic power among a handful of individuals, particularly in the armed forces. Egypt’s cronyism turned the state into ‘a conveyor belt, appropriating public funds that moved from the public domain to the pockets of the military’ (Mandour 2020). During al-Sisi’s presidency, military-owned businesses, exempted from value-added tax, flourished. For instance, Egypt’s largest cement plant, Al-Arish Cement Co., is military-owned and benefits from tax exemptions which allows them to outcompete private companies, leading to market distortions and economic inefficiencies (Reuters 2018). Most of the formal military economic sector falls outside the remit of Egypt’s audit and anti-corruption agencies, whether de jure or de facto (Sayigh 2019:18). Some of the other privileges enjoyed by military-owned businesses include the legal right to use military-designated land as equity in commercial joint ventures, the use of conscript labour, government subsidies, favourable foreign exchange rates and the ability to win contracts up to certain values on a no-bid, non-competitive basis (Sayigh 2019).

In May 2023, after pressure from the IMF to allow private investors to enter the market, United Tobacco Company, a subsidiary of the tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris International (PMI), entered the Egyptian market after winning a disputed tender. The other three tenders alleged ‘market distortion’ and ‘new forms of monopoly’ in a signed letter to Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly (OCCRP 2024). Critics argue that this process lacked transparency and fairness and that the tender was deliberately designed to favour PMI (OCCRP 2024). United Tobacco is only partly owned by PMI and the rest by an Emirati businessman and Eastern Company (OCCRP 2024). However, the remaining 38% is considered a ‘governmental issue’ and ‘classified’, and some experts have said that this indicates the involvement of companies owned by Egypt’s military (OCCRP 2024).

In the case of Egypt, trading in influence has also been facilitated through the use of wasta, a form of personal connection and favouritism. Using or invoking wasta means asking someone to intervene or mediate for you to obtain some kind of advantage from a third party, and is essentially an exchange of favours (Jackson, Tobin and Eggert 2019). Having connections and the ability to function as a wasta for one’s job is a highly prized professional asset and represents valuable social capital (Doughan 2017:3) and is often used as a mechanism to overcome inefficient bureaucracy. Nonetheless, it is known to facilitate corruption in the country and businesspeople report being reliant on wasta to operate and enjoy privileged treatment in the country (GAN Integrity 2020).

Abuse of functions and obstruction of justice

Police interference as an abuse of functions was used to suppress political opposition and consolidate power in Egypt. On 23 June 2020, police officers detained Sanaa Seif, a human rights activist who suffered years of harassment and intimidation, in front of the Supreme State Security Prosecution in Cairo (Mandour 2020). Her arrest was conducted in collaboration with the State Prosecutor, an independent judicial authority. This action is also linked to the arbitrary detention of her brother, Alaa Abd al-Fattah, who has been in arbitrary detention since 2019, accused of ‘disseminating false news’, ‘inciting terrorist crimes’ and ‘misuse of social media’ (Amnesty International 2020).

Together with the police and the military, security forces intimidate dissidents, activists and journalists. A similar case is the arbitrary detention of the businessmen Safwan Thabet and his son Sayf Thabet, owners of the Juhayna Company. The Egyptian government detained them for months after they reportedly refused to surrender their shares in their company to a state-owned business. According to Human Rights Watch, the Supreme State Security Prosecution jailed them on vague charges of ‘funding terrorism, undermining the national economy, and joining an unlawful organisation’ without presenting any evidence (Human Rights Watch 2021).

The independence of the justice sector has also been targeted through actions that have deliberately hindered due processes during the administration of justice, investigations, or legal proceedings. Targeting independent judges and auditors includes punitive transfers, smear campaigns and manipulated administration of justice. Egypt’s former anti-corruption chief and head of the central auditing organisation, Hisham Geneina, got a five-year jail term after being sacked by President al-Sisi for allegedly overestimating the country’s corruption cost. A military court found him guilty 2018 of ‘spreading information to harm the military’. When released in 2023 after serving his sentence, he was again charged with joining a terrorist group and spreading false news (AFP 2023). Finally, Al-Sharoukh reported that 35% of the new batch of appointments of assistant public prosecutors from 2011 graduates were sons of judges and advisors, indicating widespread nepotism in the sector (Saad 2014).

Sexual corruption

Sexual corruption is a form of corruption and sexual abuse in which individuals in positions of authority exploit their power to coerce others into providing sexual favours in exchange for carrying out their designated responsibilities (Basel Institute of Governance 2023; France 2022). Moreover, there is generally a lack of understanding that sextortion is a form of corruption, and the lack of sanctions is negatively influenced by the patriarchal nature of family relations in some Middle Eastern countries (Mozquer 2023).

In Egypt, while there has been no systematic study into sexual corruption in the country, there are indications in a number of news reports that this is an issue. An international law professor at Ain Shams University (a public university in Cairo) was arrested for having sex with 85 female students in exchange for helping them with an exam (Transparency International 2016). In another case, a judge in Cairo was accused of demanding sexual favours in return for biased rulings in cases he presided over in Nasr City, Cairo (GGTN 2023). The Deputy Governor of Giza requested sexual favours from a woman in exchange for issuing a decision from the Deputy Governor to stop work on a disputed plot of land, and a further case involved the arrest of an employee in the Productive Families Department at the Social Solidarity Directorate in Karf El-Sheikh, who had offered to engage in an illicit relationship with a woman in return for providing a loan for her to open a kiosk (Sabra 2024).

Electoral corruption

Free and fair elections are infrequent in Egypt. During the 2014 presidential elections, civil society organisations (CSOs) were subjected to restrictive laws and arrests and raids in an attempt to hinder their ability to operate in a free manner (Guirado 2023). And, later in 2018, potential presidential candidates raised complaints about rights violations and hindrances during the electoral process, raising concerns of favouritism of certain candidates (Guirado 2023).

In 2019, a referendum was held to attempt to amend the 2014 constitution with changes to extend presidential term limits, expand presidential control over the judiciary, and enshrine the military’s role in politics. During the election period there were reports in the working-class neighbourhoods that bribes were given - through both money and packets of food - to vote (Michaelson and Youssef 2019). The same reports were made in 2020 during the senate elections, where working-class citizens were given boxes of food rations if they could prove they had voted (Naguib 2020). Citizens were quoted as saying they did not know who the candidates were but needed the food rations (Naguib 2020).

Sectors affected by corruption in Egypt

Defence

Corruption within the Egyptian military is deeply entrenched, posing significant challenges to transparency and accountability. In Egypt, elite-state relations are centred around the Mubarak family, other political elites and the armed forces (whose influence began with the military coup of 1952), which created a systematic pattern of cronyism that persisted despite the Arab uprisings. Although the overthrow of Mubarak brought a brief period of democratic attempts, the military’s dominance was swiftly reasserted after the events of 2013, entrenching cronyism further.

The classic role of the defence sector as a mediator for social conflict disappeared and, in its place, it conducted the widespread appropriation of public funds and is used as an instrument of repression for dissenting voices (Mandour 2020). This pattern is not unique to Egypt but is prevalent across the region, with each country’s experience shaped by its specific historical and political context (Kirşanli 2023). The military’s power was further consolidated in January 2024, when a new law and amendmentf6dc44c53515 was swiftly approved which tasks the arms forces with fully coordinating with the police in guarding and protecting public facilities as well as providing the military with the same judicial powers of arrest and seizure as the police (Human Rights Watch 2024). Offences in relation to vital public facilities or buildings are now to be prosecuted in military courts (Human Rights Watch 2024).

The military’s economic involvement has also grown substantially, particularly under President al-Sisi. Al-Sisi’s economic model, focused on mega projects managed by the Egyptian Armed Forces Engineering Authority, was criticised for fostering corruption and inefficiency. These projects, such as the expansion of the Suez Canal and the construction of a new capital, often bypass civilian oversight, channelling enormous public resources through military channels and exacerbating socio-economic disparities (Egypt Watch 2022).

Corruption within the Egyptian military is so pervasive that it extends beyond the country’s borders. An example of this is the recent indictment of US Senator Robert Menendez for accepting bribes on behalf of the government to secure military aid and support foreign military sales, underscoring the military’s efforts to manipulate US political leaders for financial gain (Dawn 2023; Cabral 2024). This not only exemplifies corruption in the Egyptian military but also corruption overseas, in the US.

The Egyptian armed forces play a significant role in domestic politics. Since the 1980s, the defence sector has grown into a significant economic force, extending its influence across various civilian sectors, including infrastructure, imports and consumer goods production. However, the military’s financial involvement is often opaque. Anecdotal evidence and insider accounts also suggest extensive and routine corruption within defence sectors involved in procurement, licensing and public contracting. Business transactions owned by military agencies are conducted in secrecy, facilitating corruption and preventing citizen oversight (Human Rights Watch 2020).

Particularly since the nationalisation reforms of the 1960s, military economic activities captured a disproportionate share of public revenues and remained mainly outside the purview of Egypt’s audit and anti-corruption agencies (Sayigh 2019). Anecdotal evidence and insider accounts reveal extensive and routine corruption, particularly in procurement, public contracting and services (Sayigh 2019). Reports indicate that military businesses span diverse sectors such as infrastructure, chemical manufacturing and food production and are not subject to the same financial disclosure standards as other state-owned enterprises (Human Rights Watch 2020).

Transparency and accountability in military-owned businesses are therefore crucial for addressing corruption and mismanagement, squandering public resources that could otherwise be invested in essential services like healthcare, housing, food and social protection. However, effective implementation of transparency measures remains a significant challenge in the country.

Despite the widespread corruption cases in the Egyptian military, public trust in this institution remains paradoxically high. According to the Arab Barometer and other indices, public confidence in the military starkly contrasts with the diminishing trust in legislative, executive and judicial institutions. This disparity highlights a severe imbalance in civil-military relations and suggests that, while citizens may rely on the military for stability, this dependence undermines democratic governance and civilian oversight (Al-Ghunaimi 2021).

Education

Corrupt actions vary depending on the hierarchical level, with some cases focusing on a single level while others require coordination across multiple levels, indicating systemic issues. In the education sector, corruption spans from the micro to the macro level. At the micro level, reports highlight incidents such as forced donations from parents, diversion of resources intended for school meals, undeserved financial incentives for staff and teachers selling exams (Fayed 2019). Research misconduct in Egypt, such as authorship issues, plagiarism, unethical issues and questions and the review process and conflict of interest, are the highest of the North African region (Sawahel 2022). Corruption within the education sector exacerbates disparities in accessing quality education, particularly for disadvantaged and marginalised groups, undermining the credibility of educational institutions, eroding public trust and diminishing the quality of education provided (Fayed 2019; Sobhy 2023).

Another significant corruption case in the education sector involved the minister of education’s staff spending of EGP222,000 (around US$4,600) on personal meals over a year, as reported by the central auditing authority (Hafez 2014). The minister’s adviser also received unjustified financial bonuses (Abd El Aleem 2014). To further illustrate the pervasive corruption and suspicions within the sector, Ahmed Abd al-Khaleq, the first education minister appointed by Egyptian President al-Sisi following his 2013 coup, faces serious corruption allegations for actions taken between June 2014 and September 2015 (Middle East Monitor 2022).

Reports indicate that the first education minister, who was former head of Mansoura University, committed three financial violations between 2014 and 2015, including receiving significantly higher compensation than customary for similar positions at other universities (Middle East Monitor 2022). A government regulatory body confirmed that the excessive payments to the former head of the university were unlawful (Middle East Monitor 2022), highlighting the pervasive financial misconduct and abuse of power by officials.

Following Fayed (2019), the main sectors and experiences of corruption in Egypt’s education sector can be found at different levels. Corruption operates at a ministerial level through kickbacks, favouritism in hiring, admission, appointments and promotions. At the directorate level, these include diverting school supplies to the private market, favouritism, overlooking school violations or hiring ‘ghost’ teachers.

The Sharqia governorate witnessed the irregular appointment of 1,387 new teachers to a school which had only 183 students. Consequently, an unequal student-to-teacher ratio of 1:7 emerged. Shockingly, many of these teachers were even working abroad in Italy, and no officials were held accountable, highlighting the widespread bureaucratic complicity in corruption (Hafez 2013). This case serves as a stark example of how informality paves the way for clientelism and the extensive dysfunction within the school system. These ghost workers add to instances of ‘absenteeism, engaging in illegal forms of punishment, involvement in extra-legal tutoring duties, facilitating cheating, and presenting inaccurate data about student grades, attendance, and various activities’ (Sobhy 2023).

There are instances of corruption including the imposition of unauthorised fees, diversion of funds, inflation of school enrolment rates, students siphoning school supplies and selling test scores and grades at the micro level in the classroom. This led to a growing demand for private tutoring, which was further fuelled by the decline in teachers’ real salaries. Public schools became overcrowded, so students turned to private tutoring centres where ‘tutors rose to fame by accurately predicting questions, whether through experience or by greasing government palms’ (Yee 2023). The ministers of education have condemned this behaviour as it violates the principle of equity among students. This parallel education system perpetuates permissiveness and corruption within the education system (Sobhy 2023).

Health

Corruption in Egypt’s health sector significantly undermines the quality, accessibility, and equity of healthcare services. Bribery for receiving timely treatment, embezzlement of funds, inflated contracts, nepotism and ghost salaries have all been reported. Addressing this issue requires urgent and comprehensive reforms focused on enhancing transparency, accountability and ethical practices within the sector. Effective anti-corruption measures are crucial to improving healthcare outcomes, restoring public trust and ensuring that resources are used efficiently to benefit the entire population.

For instance, in 2022, an Egyptian court handed down a 10-year sentence and a fine of EGP500,000 (around US$10,500) to Mohamed al-Ashhab, former health minister Hala Zayed’s ex-husband, for corruption. Al-Ashhab, a senior official in Egypt’s largest state-owned life insurance company, was arrested for accepting an EGP5 million (around US$105,000) bribe from the owners of an unlicenced private hospital. The bribe aimed to secure a licence for the hospital despite its failure to meet the necessary standards (Tabikha 2022). Additionally, Mohamed Beheiry, a former health ministry’s licensing department official, was sentenced to one year in prison, while two intermediaries, Attia al-Fayoumy and Hossam al-Din Foda, were acquitted (Tabikha 2022).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, patients were given old counterfeit masks in at least 15 of the 27 isolation hospitals used as quarantine facilities (El-Sayyed 2020). Moreover, the organ trade in the Egyptian health sector is a deeply troubling issue and become an economic lifeline among the most underprivileged citizens, leading to serious ethical concerns. Political indifference and non-enforcement of sanctions have allowed this trade to become part of the supply chain for the global transplant industry (Columb and Moniruzzaman 2024). The casual disregard for the business of organ sales, known as ‘grey corruption’ – a potentially unethical activity that does not elicit significant concern or public outrage (Heidenheimer 1996) – underscores the urgent need for action to address this issue. The establishment of medical committees and amendments to criminal legislation have failed to curb the organ trade. In Egypt, sanctions have been used by criminal groups to silence their victims, with migrant ‘donors’ threatened with arrest or detention if they report abuses. While medical committees were established to regulate this activity, they were used to legitimise and effectively launder illicit transplants involving doctors, nurses and professor members of an ‘organ trafficking ring’ (BBC 2016a).

The failure to effectively implement legislation is symptomatic of state and non-state actors’ unlawful abuse of power. District hospitals in Egypt are overcrowded, understaffed, and under-resourced, with 62% of patients paying privately (through household out-of-pocket payments) for healthcare procedures (Khalifa et al. 2022). Those who cannot afford to pay out of pocket are effectively denied access to basic healthcare, not to mention costly transplant services. Following the same logic as private tutoring, citizens must pay for basic services otherwise provided for free by the government.

Local government

Corruption in Egypt is also prevalent at the sub-national level exacerbated by the complexity of the local administration system. The system’s intricacy arises from several factors, including the vast number of administrative levels and units, which total 27 governorates, 186 centres/municipalities, 225 cities, 85 districts and 4,737 villages. The overlapping responsibilities between local and central government levels lead to ineffective communication and cooperation, contributing to a bloated state apparatus. Moreover, those holding posts in local governments are largely drawn from the military, police or security agencies (TI UK 2018:16).

For instance, the governor’s authority is limited and ill-defined, resulting in arbitrary structural changes that depend on the personal philosophy of each governor. This ambiguity, with unclear mandates for high-ranking positions and a lack of standardised procedures, prevents effective accountability and fosters corruption within the local governance framework (Gamal El-Din et al. 2018).

Excessive centralisation is another major factor contributing to corruption in Egypt. It ranks 114 out of 158 countries in decentralisation and government closeness to the people. This feature limits local decision-making power and fiscal autonomy, leading to an unequal distribution of resources and poor service delivery. The central government’s reluctance to delegate authority hampers the development of human resources at the local level and fosters a dependency among local officials on the central government (Maksym and Shah 2014). This situation widens developmental gaps and increases poverty levels, particularly in Upper Egypt, thus perpetuating a cycle of inefficiency and corruption (Gamal El-Din et al. 2018).

The legal framework governing local administration in Egypt poses a significant barrier to effective governance and anti-corruption efforts. Many local administration operations, such as granting permits and implementing projects, are susceptible to manipulation due to the lack of clear, coordinated laws. Egyptian local governments regularly experience instances of expediting or stalling procedures through unofficial payments or delays. In November 2023, a government official was arrested for attempting to extort a bribe from an investor to approve a land transfer worth over US$1.6 million. Furthermore, a police officer and a traffic department official were charged with operating a ring that forged documents for impounded vehicles to sell them illegally (Hassan 2024).

Building collapses are far too common in Egypt. The collapse of a five-storey building in Cairo in 2023 killed 14 people and did not have a construction permit (Hassan 2023). Weeks before, a 14-storey building in Alexandria collapsed, which killed one and injured dozens more (Hassan 2023). There is reportedly widespread corruption in issuing building permits and bribes are often paid to officials to turn a blind eye to building violations (Hassan 2023). A study conducted by the Egyptian Centre for the Right to Housing revealed that there are 1.4 million properties on the verge of collapse across Egypt. Unofficial estimates strongly indicate that over 7 million properties violate building codes (Hassan 2023).

Finally, the legislative framework often appears as mere political declarations without practical enforcement mechanisms. Effective reform requires addressing these legal bottlenecks, ensuring clear statutes and fostering coordination across different tiers of government to enhance accountability and transparency (Gamal El-Din et al. 2018).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework in Egypt

The following sections provide an overview of the current legal and institutional anti-corruption framework in Egypt. It should be noted that, while there are several developed anti-corruption laws and responsible institutions in the country, the existing legislation is reportedly unevenly enforced, which effectively enables government officials to ‘act with impunity’ (GAN Integrity 2020; US Department of State 2022).

International conventions and initiatives

Egypt ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), the first legally binding international anti-corruption instrument providing a comprehensive framework for preventing corruption, promoting international cooperation and facilitating asset recovery. Egypt signed the UNCAC in 2003 and ratified it in 2005 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2004a). However, compliance with the UNCAC has been inconsistent since the 2011 revolution (GAN Integrity 2020).

The country also signed the legislative guide for the UNCAC, the mechanism for the review of implementation of the UNCAC and the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) and its supplementary protocols. The latter convention, along with its supplementary protocols, compels countries to criminalise practices such as human trafficking, migrant smuggling and the manufacture of illicit firearms and promotes international cooperation in countering organised crime networks that often facilitate corruption. Egypt signed this convention in 2000 and ratified it in 2004 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2004b).

Egypt is also part of the Arab Anti-Corruption Convention, a regional initiative led by the League of Arab States to counter corruption in Arab countries. It is a collective commitment to establish legal and administrative measures for preventing and punishing corruption, encouraging cooperation among member states in areas such as law enforcement and asset recovery (League of Arab States 2010). The anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing for judges and prosecutors of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) focuses on enhancing the capacities of judges and prosecutors to understand and implement effective anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures. It includes training and resources to handle cases related to financial crimes (Financial Action Task Force 2018).

The country is also a member of the Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF), a regional body affiliated with FATF, aligning to its anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) frameworks with FATF standards. Egypt is considered generally compliant with the FATF Recommendations (as of 2021), but corruption as well as illicit trafficking in narcotics and arms are noted as being pervasive risks in the country in their most recent country report (MENAFATF 2021:5).

Domestic legal framework

According to Egypt’s Administrative Control Authority (ACA), the most important legislation in measures to counter corruption are: the penal code (Law No. 58 of 1937), with dedicated chapters focusing on bribery, misappropriation of public funds, aggression against public money, treachery and forgery; the criminal procedure act, (Law No. 150 of 1950), which specifies the roles and responsibilities of investigating authorities and judicial officers, detailing the processes for arrest, search, seizure and disposal of seized items; and the illicit gains law (Law No. 11 of 1968), addressing the concept and penalties of illicit enrichment. Additionally, the police authority law (Law No. 109 of 1971) addresses crimes related to public funds, such as counterfeiting, forgery, bribery, influence-peddling, illicit gains, embezzlement and money laundering. However, the anti-bribery framework is reportedly inconsistently implemented (GAN Integrity 2020).

Other corruption related crimes are regulated by the tenders and bidding law (ensuring transparency and fairness in the execution of supply and contracting by government bodies); the money laundering law (Law No. 80 of 2002), which covers measure to curb money laundering activities in Egypt and overseas; the conflict of interest law (criminalises conflicts of interest among government officials, requiring them to relinquish conflicting interests or leave their positions); the Central Auditing Agency law (responsible for the financial oversight of public funds); and the leadership positions law (ensuring individuals in leadership roles are appointed through transparent and fair processes, preventing nepotism and favouritism).

The administrative prosecution and disciplinary courts law governs the operations of the administrative prosecution in terms of oversight, examination, and investigation of public officials, and the Administrative Control Authority Law is responsible for examining and investigating administrative deficiencies, detecting administrative, technical and financial system violations and proposing solutions. The central agency for organisation and administration law aims to enhance the civil service and ensure fairness in employee treatment, while the Police Authority Law addresses crimes related to public funds, such as counterfeiting, forgery, bribery, influence-peddling, illicit gains, embezzlement and money laundering. This department is crucial in countering financial crimes and protecting public assets (ACA 2024a).

The judiciary law (Law No. 46 of 1972) regulates the administration of justice and the organisation and functioning of courts, including the appointment, promotion, transfer, secondment and reassignment of judges. The state council law (Law No. 47 of 1972) organises the state council, detailing the formation and hierarchy of positions and types of trials (administrative, disciplinary and high administrative). The state lawsuit authority regulation law legislates for an independent judicial body representing the state in lawsuits and defending public funds, domestically and internationally.

Other regulations, according to the Administrative Control Authority, include: the central bank and banking system law (monetary, credit and banking policies); the competition regulation and prevention of monopoly practices law (rules for fair competition among economic units, ensuring market accessibility and preventing monopolistic practices); the general authority for financial control law (protecting customer rights in non-banking financial markets).

Finally, the civil service law (Law No. 81 of 2016) covers the appointment, job classification, performance evaluation, transfer, promotion and disciplinary measures of public servants, and the public agencies legal departments law (Law No. 47 of 1973) regulates the legal departments of public agencies and bodies, ensuring they perform the necessary legal activities to support proper functioning, production and services.

Institutional framework

Egypt’s anti-corruption institutional framework comprises two central bodies: the Public Control Agency and the External Control Agency (ACA 2024b). The Public Control Agency is primarily represented by the Administrative Control Authority (ACA). Established in 1964, the ACA is Egypt’s independent general oversight body exercising administrative, financial and criminal control over public bodies. It plays a central role in countering corruption by addressing issues that impede justice, co-formulating and implementing national anti-corruption strategies and raising awareness about the harmful effects of corruption (ACA 2024c). As a long-standing authority, the ACA is dedicated to maintaining integrity and accountability within the public sector. (ACA 2024c). The anti-corruption entities in Egypt are often criticised for lacking independence from the government and military (OCCRP 2020).

The External Control Agency includes several institutions, such as the Central Auditing Agency, the Ministry of Finance agencies and units (financial controllers), the Central Agency for Organization and Administration, the Administrative Prosecution Authority, the Illicit Gains Authority, the General Department for Combating Public Funds Crimes (Ministry of Interior), the Anti-Money Laundering Unit, the Financial Regulatory Authority, the National Coordinating Committee against Corruption chaired by the prime minister and the National Coordinating Subcommittee against Corruption headed by minister and chair of the Administrative Control Authority.

The Central Auditing Agency (CAA), established in 1942 as a pivotal organisation responsible for monitoring all government revenue and expenditure. Originally designed as an internal watchdog, the CAA’s head is appointed by the president for four-year terms and cannot be dismissed, ensuring its operational continuity (Baheyya Blog 2016). In 1988, the CAA’s auditing powers were significantly expanded to include the oversight of political parties, trade unions and professional associations (Baheyya Blog 2016). Reports have been made of the CAA being deliberately misleading on the cost of corruption and wasted funds in the country (BBC 2016b).

There are a number of additional government agencies that oversee anti-corruption in Egypt. The Ministry of Finance also plays a critical role through its comprehensive financial oversight and policy development. Tasked with formulating and developing financial policies and plans, the ministry coordinates budgets, rationalises government spending, and improves tax systems to align with the country’s economic and social objectives. This central financial authority prepares the state’s general budget projects. It ensures its alignment with broader national goals, positioning it as a key player in promoting fiscal transparency and accountability (Ministry of Finance 2024).

The Ministry of Finance’s supervisory responsibilities are crucial for its anti-corruption mandate. It supervises the implementation of the state’s general budget and exercises control and technical supervision over financial and accounting entities, ensuring compliance with relevant laws and regulations (Ministry of Finance 2024). By overseeing financial transactions and budget execution, the ministry works to prevent the misappropriation and misuse of public funds, which plays a pivotal role in curbing financial misconduct within government operations. However, there have been several corruption scandals involving the Ministry of Finance, such as an accountant charged in 2024 for offering and receiving bribes (Al-Qamash 2024) and recent corruption allegations made regarding the finance minister (Ghad News 2024).

The Central Agency for Organization and Administration (CAOA) in Egypt plays a role in the nation’s anti-corruption efforts by aiming to reform and enhance the efficiency of governmental administration. Established by Law No. 118 of 1964, this institution is an independent entity affiliated with the council of ministers (State Information Service 2023). Its primary objective is to implement administrative reforms, raise performance levels across various state units and ensure that government agencies fulfil their responsibilities effectively and justly (State Information Service 2023).

The CAOA’s anti-corruption initiatives include developing and proposing laws and regulations concerning the civil service, ensuring their implementation and providing technical oversight. This involves regularly inspecting personnel departments, developing equitable systems for employee selection and promotion, and proposing policies for salaries and bonuses that promote fairness and transparency (State Information Service 2023). By setting and maintaining high standards for governance and accountability in civil service practices, the CAOA contributes significantly to reducing corruption opportunities within Egypt’s government apparatus.

The Administrative Prosecution Authority (APA) in Egypt is critical in the country’s anti-corruption framework, as Law 117/1958 mandates. This institution is tasked with monitoring and investigating administrative and financial crimes among civil servants across all levels of government. The APA investigates and prepares cases for prosecution, handing over offenders to the criminal courts. Additionally, it functions as an internal whistleblowing platform where public officials can report incidents of corruption. This dual role of prosecuting and providing a reporting mechanism enhances the APA’s effectiveness in countering corruption and upholding integrity within public service sectors (State Information Service 2024).

The Illicit Gains Authority in Egypt oversees the financial integrity of public officials and employees. Tasked with the periodic examination of financial disclosure statements, this authority ensures transparency and accountability across various state bodies. It actively investigates any complaints about illegal wealth accumulation by civil servants stemming from the abuse of public functions (United Nations 2020). Empowered with substantial legal authority, the Illicit Gains Authority can take custodial control over the assets of individuals under investigation, ensuring that these assets remain untouched until the completion of inquiries (United Nations 2020).

The General Department for Combating Public Funds Crimes, operating under Egypt’s Ministry of Interior, protects the national economy and public resources (United Nations 2020). It addresses various economic crimes, including bribery, influence trading, fraud, forgery, money laundering and crimes related to illegal gains and currency smuggling. As a judicial control authority governed by police force law and the code of criminal procedure, the department’s members are provided with the powers of judicial officers (United Nations 2020).

The Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism Unit (EMLCU), established under Egypt’s anti-money laundering law (Law No. 80/2002), is crucial in safeguarding the financial system against illicit activities. The unit collaborates with domestic and international financial investigation bodies to scrutinise and investigate suspicious activities, ensuring compliance through rigorous oversight and coordination with judicial and other relevant authorities (United Nations 2020). By developing and enforcing regulations and procedures, EMLCU actively prevents money laundering and the financing of terrorism, contributing to the integrity and stability of Egypt’s economic framework (United Nations 2020).

The National Coordinating Committee for the Prevention and Combating of Corruption, established under Prime Minister’s Decision No. 2890 of 2010, is chaired by the prime minister and includes key ministers and heads of major governmental bodies (United Nations 2020). This high-level committee ensures that Egypt adheres to international anti-corruption conventions, formulating policies that align with global standards and coordinating national efforts to fulfil international obligations (United Nations 2020). Its responsibilities also extend to regularly assessing and enhancing domestic legal frameworks to ensure they effectively prevent and counter corruption, thus maintaining integrity within Egypt’s public and private sectors (United Nations 2020).

Finally, the National Sub-Coordinating Committee for Preventing and Combating Corruption, established under Prime Minister’s Decision No. 1022 of 2014, is an essential component of Egypt’s anti-corruption framework. Chaired by the head of the Administrative Control Authority, this committee comprises representatives from key ministries and governmental bodies (United Nations 2020). Its primary objective is to develop and oversee the implementation of the national anti-corruption strategy, aiming to eliminate corruption in various sectors of the state apparatus (United Nations 2020). With a wide range of powers and responsibilities, the sub-committee receives reports on corrupt activities, investigates perpetrators and proposes solutions to eradicate corruption while promoting integrity and transparency within society (United Nations 2020). It designs training programmes and workshops to enhance the capacities of individuals responsible for preventing and curbing corruption, and coordinates with state agencies to develop unified training plans (United Nations 2020). Furthermore, the committee studies international best practices to counter corruption in modern administrative systems, leveraging this knowledge to develop recommendations for enhancing integrity and transparency within Egyptian society and raising awareness about the detrimental effects of corruption among citizens (United Nations 2020).

There are numerous bodies which monitor corruption in Egypt, a number that exceeds many other countries. This has led to some experts to point out that this may indicate a weakness in the government’s administrative apparatus (Middle East Monitor 2024). Despite all these oversight and anti-corruption agencies, corruption continues to be a widespread issue in the country. There have even been notable cases of officials working in these oversight agencies being charged with corruption themselves, indicating a deeper problem. For example, a corruption case in 2023 involved the director of the Illicit Gains Department who was charged with receiving bribes in in exchange for letting customs deals and transactions fall through (Middle East Monitor 2024).

Other stakeholders

Civil society

Mirroring other nations in the MENA region, authorities actively suppress dissent and stifle the civil space, with restrictions on NGOs. Egypt’s civil society environment is severely restricted and worsened in the post-revolution period. In 2014, article 78 of the country’s Penal Code was amended with the aim to prevent foreign funding of individuals and local organisations operating in Egypt (Sadek 2014). The amendment means that any individual requesting or receiving money or equipment from a foreign country or foreign private organisation with the aim to pursue acts harmful to national interest or destabilise general peace will be penalised with a life sentence and a fine up to $69,000 (Sadek 2014). Members of civil society voiced concerns from the outset of the amendment, stating that the amended article could easily be misused to arrest human rights defenders and imposes an unjustified restriction on the work they do (Sadek 2014).

The 2017 NGO law also imposes unwarranted restrictions on the right of freedom of expression and limits the operations of civil society organisations. A new administrative body, including members of the security forces, oversees NGO registration, activities, funding and dissolution (Amnesty International 2023). As of 5 April 2023, the minister of social solidarity announced that 35,653 NGOs had registered under the 2019 NGO law. Several NGO workers have been unfairly imprisoned and given sentences on false charges, such as ‘spreading false news’, including Mohamad Baker, the founder and director of Adalah Centre for Rights and Freedoms, and Ezzat Ghoneim, founder of Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms (Amnesty International 2023). Before the 2019 law, the authorities had stated that there were 52,500 civic groups in the country (Amnesty International 2023). Only 35,653 registered after that, and those who did reported that the authorities have either delayed or refused to approve their funding or projects (Amnesty International 2023).

Two organisations currently working on anti-corruption awareness are the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) and the Arab Anti-Corruption and Integrity Network (ACINET). However, the limited civil society that remains in the country operates under extremely restrictive conditions, which have worsened since the 2013 (and more recent) legislative changes.

Media

The media in Egypt plays a crucial role in uncovering corruption but operates in a challenging environment under government scrutiny, which restricts freedom of speech. Arrests of journalists had been common under Mubarak’s presidency, but reportedly systematic under al-Sisi (Reporters Without Borders 2024b). According to the organisation Reporters Without Borders, Egypt is ‘one of the world’s biggest jailers of journalists’ (Reporters Without Borders 2024b). Over 600 news, human rights and other websites are blocked in the country (Amnesty International 2024).

Media ownership is primarily dominated by the state (National Media Authority, al-Ahram, al-Akhbar and al-Gomhuria), the military (the military’s media arm) and pro-government interests (DMC Network, CBC and ONTV). This concentrated ownership heavily influences media content and severely restricts press freedom. Other private media outlets include al-Masry al-Youm and al-Shorouk, which operate under tight constraints. The independent news outlet Mada Masr, was raided by security officers in 2019 (BBC 2019).

As of June 2024, 15 journalists are in jail, convicted or pending investigations into charges of ‘spreading false news’, belonging to a ‘terrorist’ group or ‘misuse of social media’. The blogger Mohamed Ibrahim Radwan, also known as Mohamed Oxygen, has been jailed for the past five years and subjected to physical and psychological torture for covering anti-corruption protests. He was awarded the RSF Prize for Courage in December 2023 (Reporters Without Border 2024).

In 2023, Egyptian authorities released an Al Jazeera journalist who was held for almost four years in pre-trial detention (Al Jazeera 2023). He was one of a number of Al Jazeera journalists who had been detained since the 2013 coup that overthrew President Mohamed Mordi (Al Jazeera 2023). His detention was repeatedly extended on ‘baseless allegations’ and two of his colleagues remain in detention in the country (Al Jazeera 2023).

- The UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) lists several non-financial forms of corruption that do not directly involve money exchange or financial benefits but still constitute an abuse of public office for personal gain. These include trading in influence (article 18), abuse of functions (article 19), concealment (article 24) and obstruction of justice (article 25). In addition, other forms of non-financial corruption could be patronage, cronyism, conflict of interest, favouritism and bias. See more in Rose-Ackerman and Palifka (2016).

- Infitah refers to the period starting from 1967 when Egypt transitioned into a neoliberal system. Gross domestic product (GDP) increased in this time, but public sector salaries stagnated, and some government subsidies ended, which resulted in riots in 1977 (Aref n.d.).

- Law No. 3 of 2024 on Guarding and Protecting the State’s Public and Vital Facilities and Buildings and amendments to Law No. 25 of 1966 on the Military Code of Justice.