Why must illegal fishing end?

Blue economic growth underpinning Africa’s potential for sustainable development

Fisheries provide an important contribution to food and nutrition security and employment, and fishing is a sector that generates exports and foreign currency in every African country. In 2011 the value of African fisheries was estimated at US$24 billion, contributing 1.26% to overall GDP and employing 12.3 million people – 27% of whom are women. However, for decades, global fisheries have been in a difficult state, with wild fish stocks unable to produce enough seafood to keep up with demand.bb04dcf0ad83 In 2020, the FAO reported that the fraction of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels was 65.8% in 2017 and, in terms of fishery landings, 78.7% comes from biologically sustainable stocks.

Working to overcome this threat is the focus of the United Nation’s (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 14.4 to effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing; illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing; and destructive fishing practices by 2020. However, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicts that due to overfishing and the continuation of IUU fishing, Target 14.4 is unlikely to be achieved. As an example, global estimates of the impacts of illegal and unreported fishing from 2011 to 20142c5a182ef537 indicate that annual catches are between 12 and 28 million metric tons, and worth an estimated US$16–37 billion. This directly undermines the opportunity for countries to achieve a second target – Target 14.7 – which aims to increase economic benefits to developing countries from sustainable use of marine resources and, in particular, the building of sustainable blue economies.

Blue economic growth is an important concept being promoted widely across Africa. It aims not only to promote economic growth, but also increase social inclusion and the preservation or improvement of livelihoods while at the same time ensuring environmental sustainability of the oceans and coastal areas.349eaee6d614 Therefore, the impacts of not acting to stop IUU fishing are far-reaching, with the potential to undermine sustainable development well beyond the fishery sector.

Box 1: Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing

IUU fishing includes a wide variety of fishing activities that contravene national, regional, or international legal frameworks established to conserve and manage fish stocks and living marine ecosystems. The full definition of IUU fishing is provided in the FAO’s 2001 International plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing, while shorter definitions of each activity are:

- Illegal fishing includes fishing in national waters without authorisation or in contravention of the applicable national rules; violating conservation and management measures (CMMs) of a regional fisheries management organisation (RFMO); or violating provisions of an applicable international law.

- Unreported fishing includes fishing which has not been reported, or has been misreported, to national authorities or RFMOs.

- Unregulated fishing includes fishing in an RFMO area, and in contravention of the CMMs, by vessels without nationality or registered to a state that is not party to the RFMO; or fishing in areas or for fish stocks where no CMMs are applicable when the fishing is inconsistent with the registered state’s responsibilities under international law.

Joining the dots…fisheries crimes, corruption, and illegal fishing

While IUU fishing relates to different manifestations of fishing that is in contravention of national or international fisheries laws (see Box 1), fisheries crime relates to different manifestations of crime that are, in some way, associated with fishing, the fishery value chain, or the fishery sector. Therefore, while an act constituting fisheries crime may not necessarily be an act of IUU fishing and vice versa, both acts can be linked in various ways. For example, document fraud, tax evasion, and corruption can all be fisheries crimes that facilitate IUU fishing.

Corruption (defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain)2656a3683045 when occurring in connection with fishing, or the wider fishery value chain or fishery sector, is considered a fisheries crime. Corruption threatens the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks governing fisheries resources, and therefore facilitates IUU fishing. In addition, the fishery sector has specific characteristics that make it vulnerable to corruption. For example, the global transnational nature of the industry and the lack of transparency within it, and the scarcity of fisheries resources.

Research into corruption within fisheries has been carried out for some time, particularly as a subset of wider wildlife crime. For example, in 2008, Standing identified access to fishery resources as an example of how decision makers act corruptly to facilitate illegal access to wildlife resources. International negotiations and the resultant agreements have also drawn attention to the role of corruption in facilitating wildlife crime.88341178061d Yet, discussion about anti-corruption approaches to wildlife crime have generally been by anti-corruption experts and academics, and not fisheries practitioners (including those responsible for fisheries enforcement, known as monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) officials). While it is acknowledged that there are attempts to change this, with more publications and discussions specifically concentrated on corruption in fisheries, it is apparent that these are still led largely by anti-corruption experts.

Drawing from analysis and research into investigations by fishery enforcement personnel, and focusing on the situation in East African industrial fisheries, we aim to encourage discussion and awareness about corruption from an MCS perspective. The investigations explored if there was any evidence, or suspicion, of corruption having occurred. In both scenarios, the analysis then considered how the corruption occurred, where, why, and by whom. As a result of this analysis, we have proposed possible anti-corruption activities as solutions that aim to reduce the occurrence of fisheries corruption and, likewise, the occurrence of IUU fishing.

Searching for evidence in murky waters

FISH-i Africa, a fisheries MCS task force in the South West Indian Ocean (SWIO), has published summaries of 20 investigations into IUU fishing activities that they undertook within the SWIO fishery sector between 2012 and 2019. As MCS officials are normally not involved in aspects of the fishery value chain or fishery sector that occur after the fish has been transhipped or offloaded from the vessel, these summaries generally cover IUU activities occurring either before, during, or after fishing. The latter taking place during the transhipment or offloading of fish from fishing vessels.

The FISH-i Africa investigation summaries provide key events in a timeline; a map identifying locations linked to the illegalities and the investigation; and details about what worked, what needs to change, and what their Task Force did in respect of the events portrayed. The summaries also include a valuable section entitled ‘How?’, which considers the different methods or approaches that the illegal operators used, or were suspected to have used, to either commit or cover up the illegality or to avoid prosecution. This is divided into the following subsections: vessel identity, flagging issues, business practices, avoidance of penalties, and document forgery. It is the ‘business practices’ subsection that potentially involves corruption. Therefore, if an investigation identified or suspected that corruption was involved, its summary will include a reference to ‘business practice’.

A further classification of the illegal acts divides them into four ‘types’:

- Illegal fishing or non-compliance with the fisheries rules, such as fishing with illegal gear or misreporting

- Related illegality that facilitates fishing activity, such as forged documents, misuse of vessel identity, corruption, or modern-day slavery

- Associated crime that occurs within the fishery sector, such as drug or people smuggling

- Lawlessness that is a state of delinquency with the fishery sector

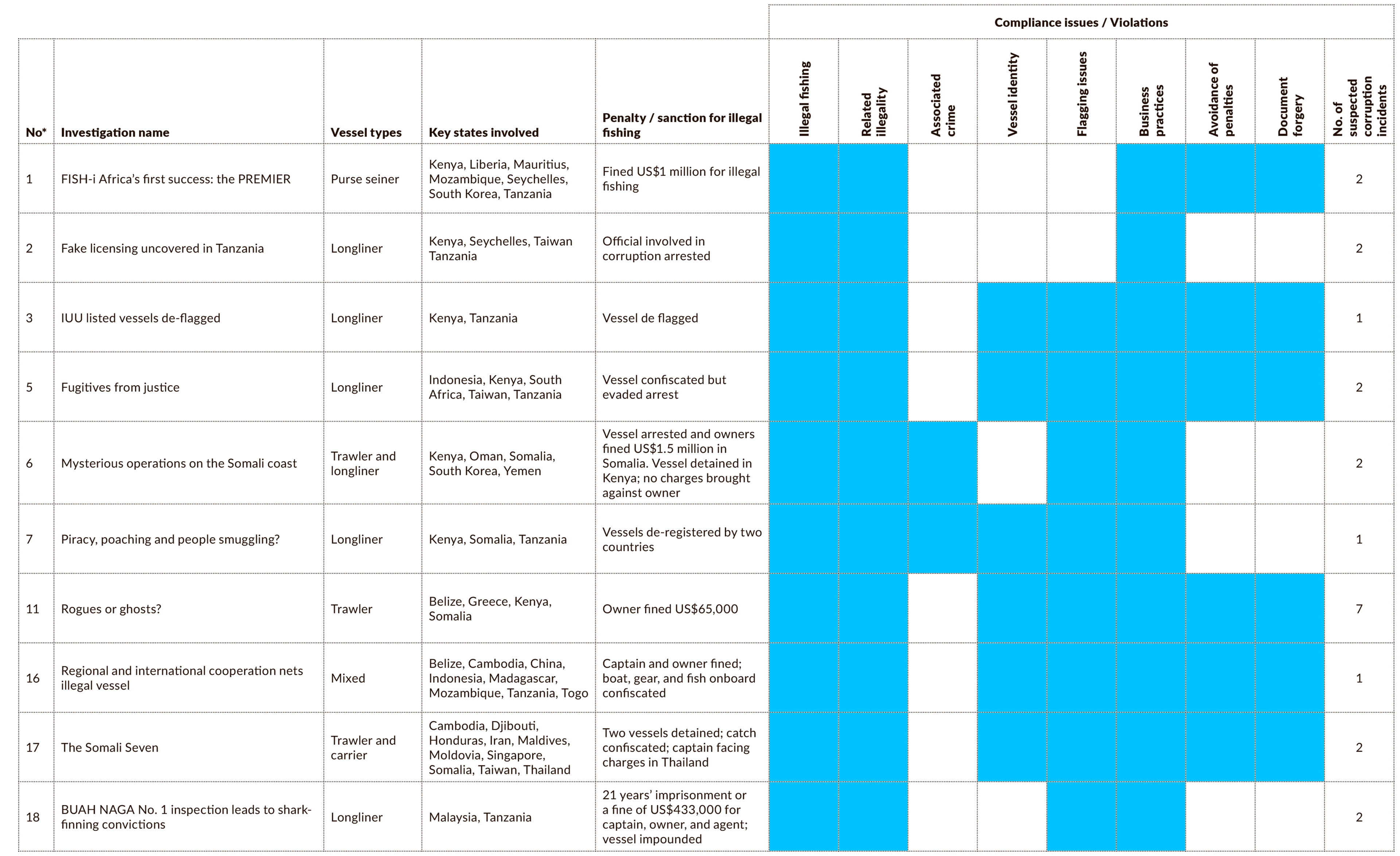

Based on these classifications of the 20 IUU fishing investigations, 14 demonstrated the three areas of interest for this study: ‘business practices’ as a method, and ‘illegal fishing’ and ‘related illegality’ as types of illegality (see Table 1).

Stop Illegal Fishing (SIF) researched and analysed these 14 investigations to explore potential links between corruption and IUU fishing. This further research and analysis was required because the focus of the FISH-i Africa investigation summaries was on the enforcement of fisheries legislation and IUU fishing. So, while ‘business practices’ was identified as a possible method or approach, the FISH-i Africa Task Force did not provide details on the suspected illegal activities, including possible corruption.

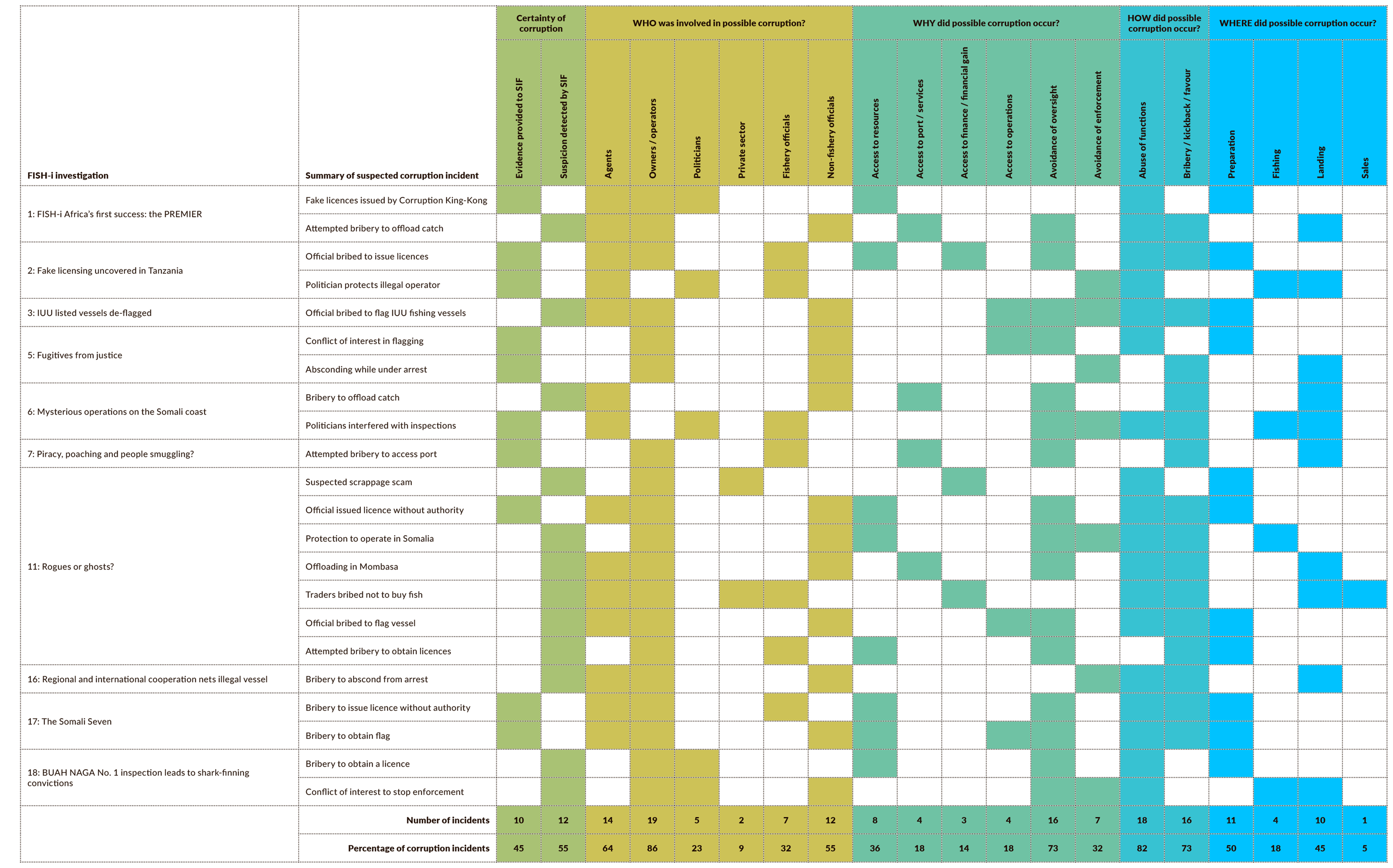

Therefore, assessment was made of the 14 investigation files – including a review of the interview notes, an assessment of correspondence, and an inspection of copies of documents (see Box 2 for an example) – and further interviews and research were conducted. From this information, ten of the investigations were identified by SIF as having an indication that corruption linked to the IUU fishing may have taken place. A total of 22 possible incidents of corruption were identified within the ten investigations. SIF recorded a summary with the details of their findings for each suspected corruption incident. This included an assessment of the certainty of corruption, who was involved, and why, how, and where the corruption occurred (see Annex 1, Table 2).

Of the ten investigations where incidents of corruption were suspected, most involved longliner fishing vessels. However, trawlers, a purse seiner, and a carrier vessel were also involved, and all were multinational with multiple flag states, coastal states, or port states involved.

While not all of the outcomes of these investigations into IUU fishing have been finalised, some have resulted in fines and vessel confiscations associated with the illegal fishing offences (see Table 1 for the investigations’ characteristics from an MCS perspective). In one investigation (Investigation 2: Fake licensing operation uncovered), charges were made that related to suspected corruption: a junior fishery official was arrested on suspicion of corruption and a warrant for the arrest of a fishery agent involved in the case was issued but not served. The fishery official was allegedly bribed and received US$5,000 per false licence issued, netting an estimated US$50,000 over three years. Although he was initially arrested, he has since been released and suspended from duties, and is believed to be running a restaurant and catering business that it is understood to have been financed from the proceeds of the suspected crime.

It is not always clear why more of the incidents of suspected corruption were not followed up by law enforcement officials, but this may be because the focus of the investigations was from a fishery law enforcement perspective rather than an anti-corruption perspective. Acting solely on the IUU fishing offences may sit more comfortably within the technical expertise of the fishery officers, and the effort and resources required to move to a criminal charge may simply become overwhelming, too complicated, and too protracted a process for fishery personnel to follow. Additionally, in many countries, the fines for fishery offences may go into the funding of the fishery authority – essentially as income – which is likely to influence the authority’s decision to follow a fishery rather than a criminal prosecution.

Box 2: How documents helped SIF to identify suspected corruption

Investigation 5: Fugitives from justice: Two suspected corruption incidents were identified by SIF in addition to the main illegal fishing case. One was in respect of a conflict of interest over flagging and the other, bribery to abscond while under arrest.

The SAMUDERA PASIFIC No. 8 and BERKAT MENJALA No. 23 are two longliner fishing vessels that were part of a fleet of ten Indonesian-flagged fishing vessels arrested off the coast of South Africa in November 2013 for suspected illegal fishing activities.

While the two vessels were under detention in Cape Town, new registration documents from the Zanzibar Maritime Authority confirmed that the vessels had been re-flagged to Tanzania, while company papers from the business register in Zanzibar showed a change in ownership of the two vessels – together these pointed to a conflict of interest in the re-flagging of the vessels. The new owner company appeared on the documents to be 51% owned by an official from the Zanzibar Maritime Authority and 49% by a Taiwanese/South African dual citizen. The official was the same person that had approved the vessels’ registrations by the Zanzibar Maritime Authority.

In December 2013, the vessels absconded from Cape Town. It was noted by the South African authorities that the vessels had been guarded by police at the time of abscondment and also at the time when, subsequent to being detained, an inspection had taken place of the vessels. They also noted that no official approval had been given for the delegation which had arrived from Tanzania to inspect the vessels, or for the vessels to set sail. Documentation from immigration print-outs of entry and exit into the country showed that the Zanzibar Maritime Authority official, who had entered South Africa along with the Tanzanian colleagues to inspect the vessels, had not left the country through official routes. This suggested that he may have left with the absconding vessels and used bribery to not only access the vessel for the unauthorised ‘inspection’ but also to facilitate its illegal departure.

Table 1: The characteristics of ten FISH-i Africa investigations that had suspicion of corruption

* For summaries see: Investigations – Stop Illegal Fishing

Corruption and illegal fishing: Looking beyond the court cases

Casting the net wide – identifying the individuals and their networks

SIF identified those who were potentially involved in the 22 suspected corruption incidents (see Figure 1) and explored the relationships, dynamics, and networks between them.

Figure 1: Individuals engaged in the alleged corruption incidents

Considering the possible involvement of government officials in the incidents, seven suspected incidents of corruption involved fishery officials, five involved politicians, and 12 involved officials from non-fishery departments or ministries. The non-fishery officials were mostly from maritime authorities responsible for flagging, or from port authorities responsible for port services. The suspected corruption incidents demonstrated that the officials from different government sectors, such as fishery, maritime, or port officials, generally had discrete sector-specific networks that rarely overlapped (see Box 3 for an example).

Box 3: Illegal fishing facilitated by suspected corruption by two officials

Investigation 17: The Somali Seven: Seven Thai-owned, Djibouti-flagged trawlers were tracked while operating illegally in the waters of Somalia in March and April 2017. Concern for the welfare of the Thai and Cambodian crews led to a rescue mission, resulting in the repatriation of 53 crew.

The first suspected incident of corruption appeared to support the illegal fishing related to the Somali fishing licences that were issued by the Ministry of Fisheries in Puntland. At the time, only the Federal Government of Somalia was authorised to issue industrial fishing licences to foreign vessels. To circumvent this, it is believed that an agent for the vessel had bribed an official in the ministry to issue a false licence. Through the agent’s close relationship to a very senior politician in Puntland, he had also gained protection for the vessels while they operated illegally in Somali waters.

Following exposure of the illegal fishing, and the related international attention gained through media coverage and INTERPOL’s investigation into the case, the vessels’ owners decided to re-flag the vessels to Somalia. A letter sent to INTERPOL by the Federal Government of Somalia, and made available to Stop Illegal Fishing, stated that a junior manager in the Federal Government’s Ministry of Ports had issued the false flagging documents to the vessels. It noted that while the documents were genuine, they were issued illegally as the official was not authorised to register vessels.

Although not proven in court, these two incidents indicate strong suspicion of corruption. While linked to the same illegal fishing investigation, they were facilitated by two different government networks – one linked to Puntland’s Ministry of Fisheries and the other to the Federal Government’s Ministry of Ports.

This observation that the networks are separated between the different government sectors is supported by the observation that a senior civil servant or politician acts as a ‘kingpin’, controlling each sector-specific network. Information provided to SIF through interviews indicated the prevalence of this type of control. In 73% of the incidents, they were facilitated by the kingpin sharing the financial gains from the suspected corruption between the various officials in his or her network, through a trickle-down system. While in 14% of them, intimidation and coercion were used by the kingpins to wield control over more junior officers. This was reported to have occurred in Kenya, Somalia, and Tanzania, where politicians or senior officials intimidated enforcement officers into not performing their duties, such as inspections or oversight and monitoring of vessel activities. Through these acts, the kingpins were reported to effectively be providing protection to the illegal operators, and therefore helping them to evade detection and possible prosecution.

Considering the possible involvement of the private sector or the fishing industry in the suspected corruption incidents, SIF deduced that vessel owners were involved in 86% of the alleged incidents and the owners’ fishery agents in 64% of them. Fishery agents are used in all SWIO ports, often required by law, to provide a range of services for vessel owners and operators, including organising licences, providing supplies, hiring crew, and exchanging information between the vessel and the local authorities. The agents appeared to be central in orchestrating many of the corruption incidents: linking the owners to the officials, making the physical contact with the government officials, and reportedly also making or offering corrupt payments. If this is correct, this relationship between agent and owner is mutually reinforcing – potentially with corrupt owners seeking out corrupt agents, and the agents protecting or hiding the owners from detection.

From Stop Illegal Fishing’s research, the same agents were identified in several of the different IUU fishing investigations and in some of the linked suspected corruption incidents. This reinforces the notion that they are the ‘door openers’ for linking corrupt government networks to corrupt industry players. This observation supports earlier work by Standing that highlighted the pivotal role that fishery agents play in fisheries corruption. Examples from the FISH-i investigations include a South Korean citizen, resident in Kenya, who has been identified as operating as both a vessel owner and agent in several of the incidents (including Investigation 1: FISH-i Africa’s first success; Investigation 6: Mysterious operations on the Somali coast; and Investigation 7: Piracy, poaching and people smuggling?). He also appeared to be involved in two others, although his role was less clear. His involvement has been reported to include applying pressure and bribing officials to reduce oversight and ignore non-compliant activities.

Another example is a dual Tanzanian and Omani citizen, previously resident in Zanzibar, who operates as both a vessel owner and agent and has been linked to several of the investigations (including Investigation 2: Fake licensing operation uncovered; Investigation 3: IUU listed vessels de-flagged; and Investigation 17: The Somali Seven). In the Tanzanian fake licences investigation (Investigation 2), Tanzanian authorities exposed evidence of corruption through internal investigations, which resulted in several arrests and charges. However, the cases are still waiting to go to court.

From the sea to the plate – uncovering the likely path

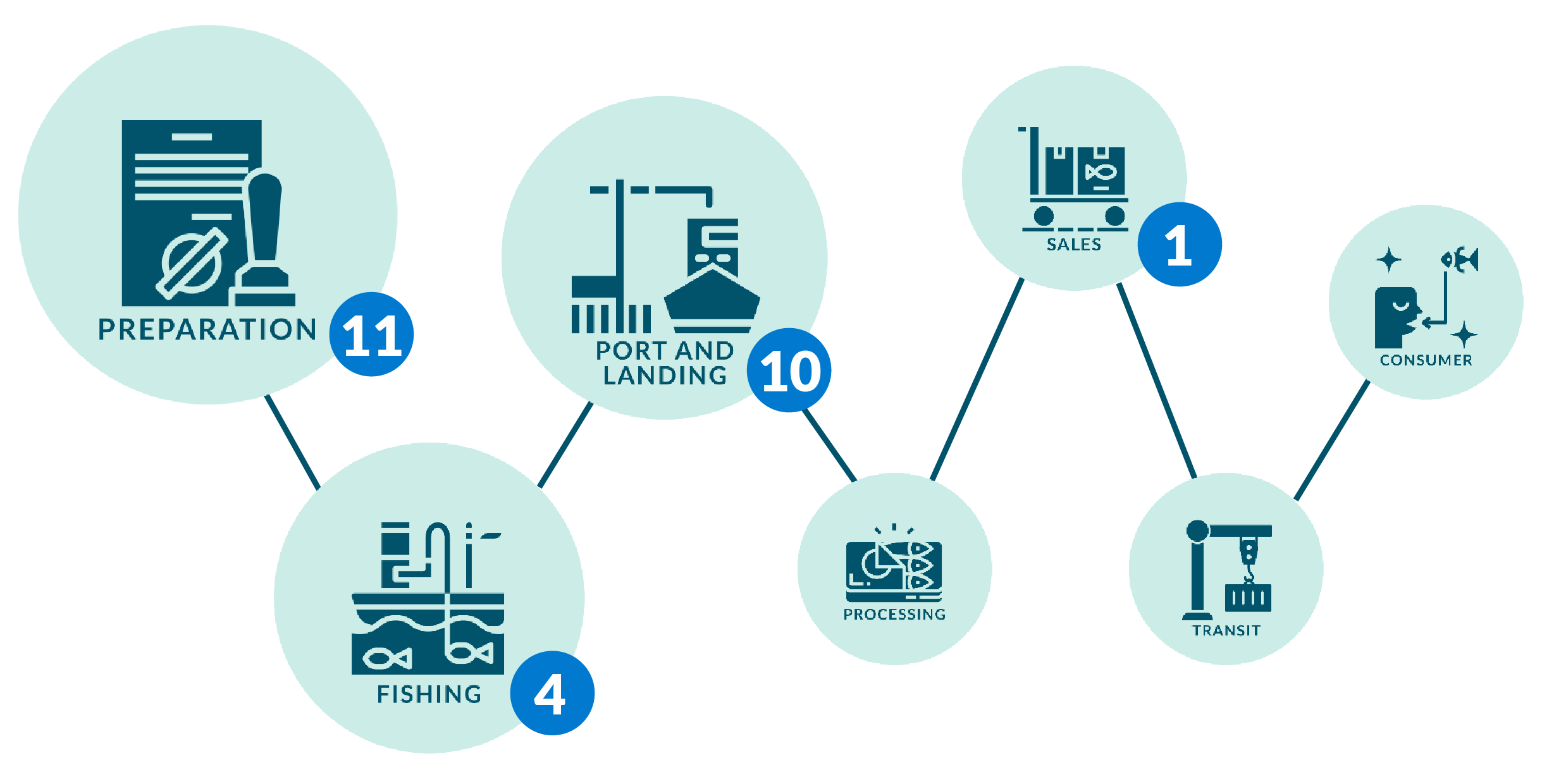

A fishery value chain is an economic concept that comprises the entire series of activities and transactions required to provide a fish or seafood product to the consumer. A fishery value chain usually includes the following steps: preparations for fishing; the actual fishing; the landing or transhipping of the catch; the processing of the catch into one or more product forms; and finally the sale, transport, marketing, and consumption of the products (see Figure 2 for an example).

Figure 2: An example of a simplified fishery value chain

Of the suspected corruption incidents, 50% were identified before the fishing took place. SIF found indications that, in four incidents, corruption was used to secure the registration of a fishing vessel when it should have been denied. For example, in Investigation 3: IUU listed vessels de-flagged, two vessel owners obtained flags from the maritime authority in Zanzibar based on the provision of false information and fake documents (the documents were provided to Stop Illegal Fishing). The correct procedure would have been for the maritime authority to validate this information with the fishery authority before issuing the registration documents. However, this did not occur, so the illegal past of the vessels was overlooked. This was reportedly due to the bribery of a maritime authority official who neglected to perform their duty and conduct checks, in collaboration with the authority responsible for fisheries, before issuing the registration documents.

In six of the incidents, corruption was suspected in respect to obtaining a fishing licence from the fishery authority. For example, in one incident a junior fishery official was bribed to provide multiple fake licences (Investigation 2: Fake licensing operation uncovered) and in another, a politician provided fake fishing licences (see Box 4).

Corruption relating to actual fishing appeared to occur in 18% of the incidents, where it is suspected to have taken place to remove oversight and monitoring – so that illegal activities would not be detected. For example, fishery officers omitting to monitor certain fishing vessels via remote vessel-monitoring systems, a practice that would be normal for legally licensed fishing vessels. This was seen, for example, in Investigation 11: Rogues or ghosts?

In 45% of the incidents, corruption was suspected to have occurred after the fishing had taken place. These incidents generally related to port authorities allowing access to the port or it services when, if correct control procedures had been followed, this should have been denied to the vessels due to IUU fishing. Other examples of alleged corruption related to activities within ports, such as an attempt to bribe a fishery official to report that the fish on board the vessel was caught on the high seas rather than in national waters – an attempt to make the fish and its offloading legal. However, the catch comprised mainly reef species, which are not caught on the high seas, and the bribe was not accepted (see Investigation 7: Piracy, poaching and people smuggling?).

In several alleged incidents, arrested vessels absconded from port, apparently without any interference from or attempt by port officials to stop them. For example, in Investigation 16: Regional and international cooperation nets illegal fishing vessel, fishing vessel STS-50 was under arrest at anchor in Maputo port in Mozambique awaiting the arrival of INTERPOL to support an inspection. Three individuals reported to SIF that the owner, via an agent, bribed officials from the maritime and port authorities to turn a blind eye and enable the vessel to escape.

Apart from one incident of suspected corruption related to the sale of confiscated fish (Investigation 11: Rogues or ghosts?), all detected or suspected corruption that occurred after fishing, happened before or during the transhipment or landing of the fish. This is the point in the value chain when a fish leaves the domain of management and oversight provided by fishery authorities and becomes a traded commodity, falling within the jurisdiction of other public authorities, such as customs and tax authorities. This is likely to be the reason why the corruption incidents identified by FISH-i Africa’s IUU fishing investigations were concentrated in the early stages of the fishery value chain, because FISH-i’s Task Force comprises fishery officers. From a fishery management perspective, if IUU fishing has taken place and not been detected before the fish is landed, the fish will then be whitewashed into the legitimate value chain and appear to have been legally caught.

Box 4: Corruption King-Kong facilitates illegal fishing licences

Investigation 1: FISH-i Africa’s first success: This revolved around the fishing vessel PREMIER and became a high-profile investigation with significant results, including the payment of a sizeable fine to Liberia by the owner. The PREMIER, having been caught fishing illegally in West Africa with a fake fishing licence, attempted to relocate to the SWIO. However, the FISH-i Africa Task Force worked together to stop the PREMIER continuing its fishing activities, and prevented any illegally caught fish entering the market through their ports.

The fake licence issued to the PREMIER in Liberia was linked to the then House Speaker Alex Tyler, known as ‘Corruption King-Kong’. This occurred at a time when a fishing moratorium was in place and no licences were legally issued. Evidence of bank transfers made to Mr Tyler were provided to SIF and these were linked to suspected bribery payments to secure fishing licences for European Union fishing vessels operating at the same time as the PREMIER. In addition, the Ministry of Finance advised SIF that they had received no funds from the licensing of the PREMIER, increasing the suspicion that Mr Tyler had also issued the PREMIER’s fake licence. Tyler has been indicted for other corruption offences, but fisheries was not named in the public records as the basis for any of them.

Taking the bait – examining the reasons

Understanding why corruption in the fishery sector happens is difficult, partly because so few court cases and convictions take place. This results in there being limited confirmed details available for discussion and analysis. However, understanding why the suspected corruption may have occurred is important, especially as insufficient court cases and convictions does not imply that corruption has not taken place. MCS officers, such as those in the FISH-i Africa Task Force, are able to use this information to make changes to their working practices that may reduce the chances of corruption occurring in the future and facilitating IUU fishing.

The suspected corruption incidents indicated there were two reasons why fishing vessel owners or their agents used corruption: to avoid oversight or enforcement of illegal activities, or to increase profits through gaining illegal access to services (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The reasons for the alleged corruption

Avoidance of oversight occurred in 73% of the alleged corruption incidents. For example, using a port where corrupt port officials allowed the offloading of illegal catches, or the harbouring of an illegal fishing vessel by not informing the fishery officials that the vessel had docked. Alternatively, bribing a fishery inspector to avoid inspection, to not remotely track the vessel, to not monitor transhipment, or to turn a blind eye if illegalities were observed. Avoidance of enforcement occurred in 32% of the alleged incidents of corruption and related to facilitating vessels under arrest to abscond from port – enabling owners to evade related fines or confiscation of their vessel – or omitting information required to enable a conviction.

The most common example of enabling access to services to increase profits or reduce costs was bribery of officials to abuse their powers and issue false documents. For example, fishing licences and registration documents that enabled access to fishing which should have been denied. In another incident of suspected bribery, the cover-up of the false scrapping of a fishing vessel enabled the Greek owner of the GREKO 1 and GREKO 2 to access European Union subsidies that he was not entitled to (see Investigation 11: Rogues or ghosts?).

In other incidents, bribery was allegedly used to gain false licences at a cheaper price than legitimate licences, reducing operating costs and causing losses estimated at US$1 million for the government of Tanzania (see Investigation 2: Fake licensing operation uncovered). In this investigation, there was also a need to reduce oversight of the fishing vessels while they operated illegally in the waters of Tanzania, demonstrating how often the two possible reasons for corruption – avoidance and access – may be closely linked (see Box 5, for another example).

Box 5: Possible links between corruption for avoidance and corruption for access

Investigation 6: Mysterious operations on the Somali coast: This provided evidence that the POSEIDON and the AL-AMAL were fishing illegally in Somali waters, engaging in illegal transhipment at sea, and at other times offloading illegal fish in Mombasa, Kenya. It also demonstrates how the two possible reasons of avoidance and access, identified by SIF as likely to have caused the alleged corruption incidents, are closely linked.

The paperwork provided to Kenyan authorities for both vessels was not in order. Inconsistencies were found in the documents supplied by the vessels’ agent, which suggested they included forgeries and raised issues about the identity and registration of the vessels. These inconsistencies should have resulted in them being denied use of port services. However, the port authorities permitted access to the services, including offloading and re-supply, without the required approval of the fishery officers. This port access was enabled by suspected bribes paid by a known corrupt agent to port officials. This was then believed to have been complemented by a further suspected bribe provided to a senior fishery official who, in turn, informed junior fishery officials to ‘back off’ during regional investigations into the vessels. He reportedly told them to stop gathering evidence to support both legal action against the owner and agent, and the illegal fishery case in Somalia.

Something fishy is going on – recognising the behaviour

The most common manifestations of suspected corruption that SIF identified were bribery, kickbacks, or favours, which resulted in apparent abuse of function.

A common scenario was that the suspected industry player, usually the owner and/or agent of the fishing vessel, would engage in some form of bribery, kickback, or provision of favour with the government official – often, as noted previously, through a network headed by a kingpin. The payment of money was evident, if not proven. For example, via bank transfers (in Investigation 1 and Investigation 2, these were related to payments for fake licences in Liberia and Tanzania respectively), or reportedly offering cash in envelopes (such as the attempted bribery by the owner of the GREKOs in Investigation 11).

In other suspected incidents the relationship between the players was likely to have been related to kickbacks and favours, for example support provided to politicians in their political campaigns and opportunities for business deals. This appears to have been demonstrated in Investigation 5 when an official from the maritime authority in Zanzibar had 51% ownership in a company that owned two fishing vessels. This ownership was allegedly in exchange for his involvement in facilitating their evading arrest, their re-flagging, and their protection from official oversight. While this ‘arrangement’ failed in respect of the vessels being permitted to legally operate within the SWIO region, they are still operating somewhere, and those involved have not been brought to justice.

As noted by Jackson, if corruption is widespread – as in several of the countries in the SWIO – then the expectation is that people will take opportunities to act corruptly, or at least refrain from active anti-corruption behaviour. This appears to be supported by this research, as the officials involved in the suspected corruption incidents were often operational officials linked to a senior official (kingpin) who shared the corruption benefits, usually money, among the network of people within his or her ‘power’. These networks resulted in abuse of functions by various officials, as was evident in 82% of the suspected corruption incidents. Intimidation and coercion to remain silent, to not take opposing action, or to not report corruption, was identified by SIF three times (Investigations 2, 6, and 18).

Acting to stop corruption in East African industrial fisheries

Addressing corruption in fisheries in the SWIO and East Africa would be a key step towards reducing illegal fishing, and thus assisting coastal states to achieve SDG Targets 14.4 and 14.7 to eliminate IUU fishing and develop blue economic growth.

What to change: Removing the drivers that sustain corruption

Fighting industrial IUU fishing is a complex task with many uncertainties. Stop Illegal Fishing’s research suggests that in many incidents, even if not proven through court cases, corruption plays a role in facilitating industrial IUU fishing. Therefore, if countries are to fight IUU fishing, it is important to understand why this is the case. From the analysis of IUU fishing investigations undertaken by the regional FISH-i Africa Task Force, the following factors emerged that contribute, at least in part, to enabling corruption within the industrial fishery sector to take place. These factors can be assessed in order to find ways to reduce corruption.

- Established corrupt networks exist within some national governments’ maritime, port, and fishery authorities within the region.

- These networks appear to be regionally linked, and facilitated through dishonest fishery agents who operate as ‘door openers’ for illegal operators so they can manoeuvre between jurisdictions, thereby avoiding detection or conviction.

- Fragmented national fishery legal frameworks combined with weak implementation creates inconsistencies and gaps that allow corruption to go unpunished.

- Many different authorities are involved in the fishery sector. However, there is a common lack of interagency cooperation that results in unclear institutional responsibilities across jurisdictions and creates openings that are easily exploited by corrupt operators.

- The domains and powers of kingpin politicians and senior civil servants have an impact on operational officers and their ability to perform their duties, such as inspecting fishing vessels and validating information in a transparent manner.

- There is a lack of deterrence due to limited action against corruption, which is rarely disrupted by arrests or prosecutions. This is partly because of insufficient awareness about anti-corruption solutions, such as risk assessments, whistle blowers’ hotlines, or adequate training (especially for fishery officers) in detection and evidence-collection procedures.

- It is difficulty to identify an illegal fish: illegal and legal fish look, and taste, the same. Also, it is usually not the fish itself that is illegal, but the activities related to the catching of it. This makes identification of illegality, including corruption, complex – especially after the fish has been transhipped from the fishing vessel.

- Vessels at sea are far from the oversight of authorities, resulting in a ‘last frontier’ situation which enables transnational organised crime to operate at a very low risk of being caught. Links to other sinister crimes, such as human and drug trafficking, mean that fishery officers can baulk at dealing with the criminals involved, be easily intimidated, and focus only on fishery illegalities rather than other crimes such as corruption.

How to change: Moving from corruption to compliance

While many of the incidents have not been proven in court, they offer an analytical yet practical insight into how corruption may have facilitated IUU fishing in East Africa, why and where it took place, and who was involved. Considering that the SDG Target 14.4 (which includes ending IUU fishing) was set to be achieved by 2020, experience would suggest that while East African governments and their supporting partners could spend time and resources academically and practically investigating corruption, it may be wise to focus efforts on introducing and strengthening mitigating tools and approaches.

To address the factors identified as causing and maintaining corruption within the fishery sector that facilitates IUU fishing in industrial fisheries in East Africa, the following solutions are proposed. They may be applied by countries in East Africa and those supporting them, such as donor agencies.

Anti-corruption capacity building

- Introduce corruption and anti-corruption approaches into curricula for courses in fishery management and MCS across all learning types (short vocational courses, universities etc.)

- Prepare and make available material, such as manuals, to support anti-corruption behaviour and activities in fishery-related work (for examples, see SIF manuals)

- Make online information and training material on corruption and anti-corruption tools widely available, and prepared in local contexts and languages for relevant officers

- Promote anti-corruption champions and stories through awareness and media

- Establish and promote protection schemes for whistle blowers

- Build capacities for investigations and prosecutions

- Promote the implementation of corruption risk assessments and the development of risk mitigation strategies (see UNODC: Rotten fish: A guide on addressing corruption in the fishery sector)

- Involve non-fishery agencies in capacity-building programmes, including port, maritime, judiciary, and tax administrations

National interagency cooperation

- Promote national interagency cooperation and committees to ensure due diligence for the flagging and licensing of fishing vessels between different authorities, and interagency port inspections

- Encourage the development of information-sharing procedures (eg standard operating procedures) for interagency cooperation and the formalisation of these through memoranda of understanding or similar mechanisms

- Develop methods for information sharing, eg online platforms, and provide technical support to facilitate the use of such platforms

- Include an element of interagency cooperation in all fishery projects and do not focus only on the fishery authority

- Target initiatives at weak flag, coastal, ports, or crew states and assist them to strengthen – do not cherry pick

- Expose scandals and criminals and apply political, diplomatic, and popular pressure to ensure action is taken against all corrupt operators involved

- Support multi-agency investigations into corruptions

Regulations and oversight for fishery agents

- Support the development of best-practice information and manuals for fishery agents and those overseeing them

- Encourage improved procedures and oversight of agents, including their approval by an interagency committee to ensure no conflict of interest before being certified to operate

- Advocate the requirement for agents to be accountable for the operation and performance of fishing vessels that they service

- Provide information to the fishery industry operators about the role and standard of agents, and make lists of approved agents publicly available

- Publicise, or support the publication of, information about corrupt agents and their involvement in illegal operations

Regional task forces and MCS centres

- Encourage systematic regional information exchange for fishery enforcement through MCS centres and task forces (eg the Regional SADC MCS Coordination Centre, the Indian Ocean Commission’s Patrols, and FISH-i Africa)

- Support regionally integrated operations, such as MCS patrols, and the sharing of remote tracking information and inspection results

- Promote the development of regionally negotiated standards and shared implementation procedures to assist in raising the bar for expectations and to limit loopholes in enforcement

- Foster the creation of regional champions and the building of trust between players, to create a culture and a social norm to motivate individuals to stand against corruption

International cooperation

- Support national links to INTERPOL to assist in fighting transnational organised crime

- Implement international standards, for example by: supporting implementation of the FAO Agreement on Port State Measures; sharing registration documents and fishing authorisations; and populating international registers, records, and lists (owners, companies, vessels)

- Encourage media coverage of all corruption cases in the fishery sector to act as deterrence

- Fund support for, and provide technical expertise to, countries to ensure that corruption investigations can take place

Keeping it in context

- Nurture good work on local terms, eg not demanding donor systems and standards to be applied when they are not appropriate

- Support appropriate research into corruption to understand how it takes place (forms, financial flows, mechanisms used, etc.), working in the countries where the issues are occurring

- Focus support efforts on known hot-spots for corruption where a high local impact can be expected, and work with people who can take effective action in those scenarios

Annex 1

Table 2: FISH-i investigations: Analysis of incidents of suspected corruption

- Fish consumption has spiked 122% in the last three decades, according to the United Nations. See: FAO, 2020.

- These are updated estimates based on original estimates from Agnew, D.J. et al., 2009.

- See World Bank and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017.

- U4 definition: https://www.u4.no/terms.

- Such as the London Declaration on Illegal Wildlife Trade (2014), the Kasane Statement (2015), and the African Strategy on Combating Illegal Exploitation and Illegal Trade in Wild Fauna and Flora and its Action Plan (2015).